POSTING CREDIT NOTE* I should have given proper credit and a link to the author of this story Mr. Bennet Stevens, thanks Benn for the wonderful article. Here is a link to his site where the story originated. Check out the photographs on the link as well, I especially like the work done at the Cambodian AIDS clinic.

http://www.bennettstevens.com

Here is a brief Bio of Bennet Stevens:

Bennett Stevens is a writer/photographer and co-founder of

Breakfast with Salgado

by Bennet Stevens

OK, so breakfast is a bit of a misnomer. More like coffee and crumpets for 20. The occasion was a morning workshop put on by Fotovision.org, a San Francisco Bay Area non-profit organization dedicated to helping documentary photographers create, edit, fund and distribute their work worldwide.

And so we were gathered at "the feet of the master" in a small studio across the street from Pixar Animation; a gaggle of "emerging" photographers joined by Pulitzer Prize-winning photojournalist, Kim Komenich of the San Francisco Chronicle; multi-award-winning social documentary photographer, Ken Light; renowned photo editor and longtime Salgado collaborator, Fred Ritchin of Pixelpress.org; and a small film crew.

I sit directly down the long rectangular table from Salgado; he is at the head, I at the ass end, a perfect juxtaposition of our skill levels. He looks good, a vibrant 60, blue eyes shining under a white baseball cap that covers his perfectly baldpate. After a brief introduction, Sebastiao, good naturedly, informs us that he has never conducted a workshop and has little idea of where to start. So he asks us to begin by asking him questions.

And so we do. And will for the next three hours. His answers come thoughtfully, forthrightly, engagingly, lengthily. His English, though virtually fluent, is spoken with a Brazilian Portuguese accent tinged with Parisian, and is not always easy to follow. The film crew is ever lurking, the soundman perpetually swinging his fuzzy, stuffed animal (windscreen) of a mike over our heads. The wind, to the best of my meteorological abilities, is coming out of nowhere at zero kilometers per hour.

First up is a 30-something photojournalism teacher, a liberal intellectual type who poses a rather labyrinthine question, or group of questions, most of which he answers for himself. I cannot recall the first exactly, but the gist is essentially, what is your philosophy as an artist. The gist of Salgado’s answer is, “I am not an artist and so I have no philosophy as one.”

Next!

Even though Sebastiao masks it well — his actual answer is not so curt of course, and one senses that he’s dealt with these types before — he has a certain level of disdain for the over-intellectualization of photography. The journo prof's continuance amounts to pointing out a common criticism — a thorn in Salgado’s side as Fred Ritchin lets be known — that he makes beautiful pictures of people suffering, that he somehow romanticizes and even exploits it. What do you say to these critics?

I paraphrase:

Salgado: Here I am 20 years later and people are still talking about Sahel, reprinting Sahel, and of course it’s topical again since the ongoing tragedy in Darfur. If I did not make these pictures with good light and good composition, if they were not compelling, how would they now be contributing to the discussion about Darfur? The information from the Sahel book keeps circulating because the pictures are well made.

Eduardo Galeano, who along with Ritchin wrote essays that appear in Salgado’s An Uncertain Grace, explains it thus:

Galeano: Salgado's photographs, a multiple portrait of human pain, at the same time invite us to celebrate the dignity of humankind. Brutally frank, these images of hunger and suffering are yet respectful and seemly. Salgado sometimes shows skeletons, almost corpses, with dignity — all that is left to them. They have been stripped of everything but they have dignity. That is the source of their ineffable beauty… That instant of trapped light, that gleam in the photographs reveals to us what is unseen, what is seen but unnoticed; an unperceived presence, a powerful absence. It shows us that concealed within the pain of living and the tragedy of dying there is a potent magic, a luminous mystery that redeems the human adventure in the world.

A young woman, who’s worked with Steve McCurry in Tibet, asks about coping with the emotional aspects of photographing in such conditions, and if he ever questions himself. Fred Ritchin steps in.

Ritchin: People often assume—wrongly—that Sebastiao has to stay detached from the suffering, otherwise how can he cope with it. And this goes to the heart of who he is as a photographer and as a man. The last thing he wants to be is detached.

Salgado: Detachment is disaster for the documentary photographer. You must live within the situation, let it become your real life, share with the people what they are going through the best you can. Do I question myself? No, because all my ethical concerns have been decided ahead of time. There can be no room for doubt. You don’t go to take anything from anybody or to exploit them. You don’t “take” pictures, you make pictures; you make them well and use them to communicate, to help the people and the situation. Many times the suffering people in the Sahel would see me working and they would ask me to come and photograph them or a loved one as a way of helping to solve the problem. In time they come to your camera like they would come to a microphone, they come to speak through your lens.

His famous use of light is “part of who I am," says Salgado. Raised on an Amazonian cattle ranch, with dust and smoke resulting in diffuse light, and with simple structures allowing mostly chiaroscuro lighting situations indoors, this was the medium through which he came to see the world. He knows it and knows how to work with it. He will often shoot against the light, even overexposing his Tri-X up to five stops!

Salgado holds up his Workers book, just one of several multi-year projects, shuffling through the pages until he finds the famous photo of an oil worker in Kuwait after Gulf War 1. The man is seated and slumped and covered in crude, having spent a long day under black skies putting out oil fires. It’s about an 8 x12 inch image, without an unusual amount of grain. We guess the ISO was 400. Wrong! In actuality it was shot at 3200. The reason for so little grain was that the subject and the background were almost entirely black and white, with little by way of gray tones.

By this time I am stepping on Komenich’s Pulitzer feet and snapping off a few shots with my new digital Nikon. Salgado is not a fan of the digital camera. Nor is Ritchin, who, being a photo editor prefers to see the evolution of an image — and a photographer — frame by frame. The fact that digital images are so often destroyed on the spot is bothersome to him. He goes on to say how sometimes an image can remain on a contact sheet, overlooked for decades before being “discovered”. Salgado’s own documentary archive exceeds half a million images.

Karen Ande of andephotos.com, who documents the AIDS crisis in Africa, asks the question I was about to ask. I paraphrase:

Ande: Given the number of intense and emotionally delicate situations you’ve put yourself in, you must have a special way of getting people to accept you and your camera. People dying, their loved ones suffering are not always happy to see a lens pointing at them.

Salgado: This is very true, and so you must always have asked permission. Not for each time you click the shutter, but to be a part of the situation in the first place. When you first arrive it’s important to get introductions. If you go to a village or a factory or into the fields or a feeding center in the desert, you must get introduced or introduce yourself to whomever it is that can give permission in that situation. Explain yourself in a way that makes your being there important for them. It’s one thing to make ‘street shots’ here and there, but to tell a story you must get inside the story and live with the story, in a sense becoming part of he community. This also allows you to know when not to be pointing your camera, when it would not be appropriate. There are times I do not make the picture, out of respect for the people and the moment.

With this Salgado draws a Bell curve on a pad of paper. The bottom of the near curve is where you — the photographer — approach and first enter a given situation. Here on the street you may be using a longish lens. Then you make your introductions. You explain yourself and most importantly, get permission.

At first the shooting can be very difficult, a steep, slow trudge up the curve. But after a few days or a week, as people become accustomed to you and your camera, you climb the curve more steadily. As you get deeper into the story your lens gets shorter. The pictures get better. When you approach the apex of the curve, there is less gravity working against you. The people have accepted you and dropped their defenses. The story enters its climax stage at the top of the curve and you are now using your shortest lens and making your best pictures. Inevitably you begin to sense a natural drop off; the story winds down. Traversing down the other side of the curve is a bit like cuddling and having a cigarette after sex. Gradually, and as gracefully as possible then, you extricate yourself from the bed of the story, giving your thanks and saying your goodbyes, while your lens (and here we must depart from the sex analogy) is once again getting longer.

Galeano: Salgado photographs people. Casual photographers photograph phantoms… Consumer-society photographers approach but do not enter. In hurried visits to scenes of despair or violence, they climb out of the plane or helicopter, press the shutter release, explode the flash: they shoot and run. They have looked without seeing and their images say nothing.

We spend a fair amount of time discussing the “framing” of a documentary project. In other words, know what you want to do, what your project is going to be about, and that your reasons for doing it are very important to you. If they are not, the difficulties of any given situation may overcome your dedication to it, and your work will reflect it.

Do as much research as you can. Wherever possible, develop contacts for your introductions ahead of time. Again, know the heart of the story you plan to tell with your photographs. Of course you cannot know the specifics; these will take care of themselves. And of course, things are never as you expect them on the ground, so you must also be nimble and prepared to make adjustments. Keep your eyes and your mind open, but at the same time stay focused on the main threads of your story. Otherwise you may think things are going well, only to return home and discover that somewhere along the way you lost your story, and are left with only a few nice pictures.

Fred Ritchin talks about some lesser-known aspects of Salgado. About how they worked together on a project to eliminate polio worldwide, which has been very successful if not 100 percent yet. He mentions how Salgado donates time and money to Medicins Sans Frontiers (MSF) and other groups helping the developing world. How he has rehabilitated rainforest in the Amazon where he grew up. How his current project, Genesis, is a risk and a departure from his previous work, and that he is learning a new medium format camera specifically for it.

The genesis of Genesis was Migrations, or rather the despair he felt at the he end of the project. He saw so much destruction of the environment, so much greed leading to human displacement and intractable poverty in the second and third worlds that his faith in humanity was badly waning. He wanted to address the reasons for this loss of faith in a way that would help to restore it, both for him and others. Like all his other major works, this project will take several years; he estimates seven. It is these multi-year projects that set Salgado apart from other great documentary photographers.

Salgado: I conceived this project as a potential path towards humanity's rediscovery of itself in nature. I have named it Genesis because, as far as possible, I want to return to the beginnings of our planet: to the air, water and fire that gave birth to life; to the animal species that have resisted domestication and are still "wild"; to the remote tribes whose "primitive" way of life is largely untouched; and to surviving examples of the earliest forms of human settlement and organization. This voyage represents a form of planetary anthropology. Yet it is also designed to propose that this uncontaminated world must be preserved and, where possible, be expanded so that development is not automatically commensurate with destruction.

Our breakfast with Salgado is over before we know it, and it’s time for lunch without him. Fred will continue the workshop after the break. Outside, still in something of a daze of icon envy, I spot Sebastiao heading down the block and resist the urge to run after him. He is off across the bay where he will be giving a fund raising speech later that night. To think that the best "pure" documentary photographer on the planet still has to work at raising money for his projects is more than a bit daunting. Seven-year projects are not easily funded of course, but the price of his well-earned emancipation from assignment work pays for itself in many other ways. Most importantly, it gives him the freedom to express the world he sees to the world at large, to speak directly through his lens without having to endure a bad translation from some editor sitting behind a desk in New York or Paris. There will be plenty of that after the fact, when the photo-intellectuals swoop down to feed and regurgitate to the public what they are so often incapable of fully digesting for themselves.

http://www.bennettstevens.com

Here is a brief Bio of Bennet Stevens:

Bennett Stevens is a writer/photographer and co-founder of

Luminous Journeys, a travel company providing top flight

photography tours & workshops in Myanmar. Please visit

www.luminousjourneys.net for details.

Breakfast with Salgado

by Bennet Stevens

OK, so breakfast is a bit of a misnomer. More like coffee and crumpets for 20. The occasion was a morning workshop put on by Fotovision.org, a San Francisco Bay Area non-profit organization dedicated to helping documentary photographers create, edit, fund and distribute their work worldwide.

And so we were gathered at "the feet of the master" in a small studio across the street from Pixar Animation; a gaggle of "emerging" photographers joined by Pulitzer Prize-winning photojournalist, Kim Komenich of the San Francisco Chronicle; multi-award-winning social documentary photographer, Ken Light; renowned photo editor and longtime Salgado collaborator, Fred Ritchin of Pixelpress.org; and a small film crew.

I sit directly down the long rectangular table from Salgado; he is at the head, I at the ass end, a perfect juxtaposition of our skill levels. He looks good, a vibrant 60, blue eyes shining under a white baseball cap that covers his perfectly baldpate. After a brief introduction, Sebastiao, good naturedly, informs us that he has never conducted a workshop and has little idea of where to start. So he asks us to begin by asking him questions.

And so we do. And will for the next three hours. His answers come thoughtfully, forthrightly, engagingly, lengthily. His English, though virtually fluent, is spoken with a Brazilian Portuguese accent tinged with Parisian, and is not always easy to follow. The film crew is ever lurking, the soundman perpetually swinging his fuzzy, stuffed animal (windscreen) of a mike over our heads. The wind, to the best of my meteorological abilities, is coming out of nowhere at zero kilometers per hour.

First up is a 30-something photojournalism teacher, a liberal intellectual type who poses a rather labyrinthine question, or group of questions, most of which he answers for himself. I cannot recall the first exactly, but the gist is essentially, what is your philosophy as an artist. The gist of Salgado’s answer is, “I am not an artist and so I have no philosophy as one.”

Next!

Even though Sebastiao masks it well — his actual answer is not so curt of course, and one senses that he’s dealt with these types before — he has a certain level of disdain for the over-intellectualization of photography. The journo prof's continuance amounts to pointing out a common criticism — a thorn in Salgado’s side as Fred Ritchin lets be known — that he makes beautiful pictures of people suffering, that he somehow romanticizes and even exploits it. What do you say to these critics?

I paraphrase:

Salgado: Here I am 20 years later and people are still talking about Sahel, reprinting Sahel, and of course it’s topical again since the ongoing tragedy in Darfur. If I did not make these pictures with good light and good composition, if they were not compelling, how would they now be contributing to the discussion about Darfur? The information from the Sahel book keeps circulating because the pictures are well made.

Eduardo Galeano, who along with Ritchin wrote essays that appear in Salgado’s An Uncertain Grace, explains it thus:

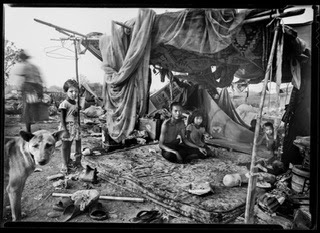

Galeano: Salgado's photographs, a multiple portrait of human pain, at the same time invite us to celebrate the dignity of humankind. Brutally frank, these images of hunger and suffering are yet respectful and seemly. Salgado sometimes shows skeletons, almost corpses, with dignity — all that is left to them. They have been stripped of everything but they have dignity. That is the source of their ineffable beauty… That instant of trapped light, that gleam in the photographs reveals to us what is unseen, what is seen but unnoticed; an unperceived presence, a powerful absence. It shows us that concealed within the pain of living and the tragedy of dying there is a potent magic, a luminous mystery that redeems the human adventure in the world.

A young woman, who’s worked with Steve McCurry in Tibet, asks about coping with the emotional aspects of photographing in such conditions, and if he ever questions himself. Fred Ritchin steps in.

Ritchin: People often assume—wrongly—that Sebastiao has to stay detached from the suffering, otherwise how can he cope with it. And this goes to the heart of who he is as a photographer and as a man. The last thing he wants to be is detached.

Salgado: Detachment is disaster for the documentary photographer. You must live within the situation, let it become your real life, share with the people what they are going through the best you can. Do I question myself? No, because all my ethical concerns have been decided ahead of time. There can be no room for doubt. You don’t go to take anything from anybody or to exploit them. You don’t “take” pictures, you make pictures; you make them well and use them to communicate, to help the people and the situation. Many times the suffering people in the Sahel would see me working and they would ask me to come and photograph them or a loved one as a way of helping to solve the problem. In time they come to your camera like they would come to a microphone, they come to speak through your lens.

His famous use of light is “part of who I am," says Salgado. Raised on an Amazonian cattle ranch, with dust and smoke resulting in diffuse light, and with simple structures allowing mostly chiaroscuro lighting situations indoors, this was the medium through which he came to see the world. He knows it and knows how to work with it. He will often shoot against the light, even overexposing his Tri-X up to five stops!

Salgado holds up his Workers book, just one of several multi-year projects, shuffling through the pages until he finds the famous photo of an oil worker in Kuwait after Gulf War 1. The man is seated and slumped and covered in crude, having spent a long day under black skies putting out oil fires. It’s about an 8 x12 inch image, without an unusual amount of grain. We guess the ISO was 400. Wrong! In actuality it was shot at 3200. The reason for so little grain was that the subject and the background were almost entirely black and white, with little by way of gray tones.

By this time I am stepping on Komenich’s Pulitzer feet and snapping off a few shots with my new digital Nikon. Salgado is not a fan of the digital camera. Nor is Ritchin, who, being a photo editor prefers to see the evolution of an image — and a photographer — frame by frame. The fact that digital images are so often destroyed on the spot is bothersome to him. He goes on to say how sometimes an image can remain on a contact sheet, overlooked for decades before being “discovered”. Salgado’s own documentary archive exceeds half a million images.

Karen Ande of andephotos.com, who documents the AIDS crisis in Africa, asks the question I was about to ask. I paraphrase:

Ande: Given the number of intense and emotionally delicate situations you’ve put yourself in, you must have a special way of getting people to accept you and your camera. People dying, their loved ones suffering are not always happy to see a lens pointing at them.

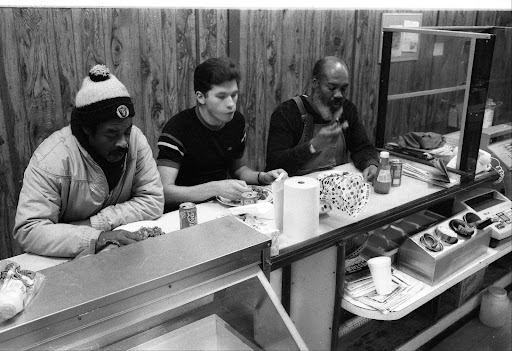

Salgado: This is very true, and so you must always have asked permission. Not for each time you click the shutter, but to be a part of the situation in the first place. When you first arrive it’s important to get introductions. If you go to a village or a factory or into the fields or a feeding center in the desert, you must get introduced or introduce yourself to whomever it is that can give permission in that situation. Explain yourself in a way that makes your being there important for them. It’s one thing to make ‘street shots’ here and there, but to tell a story you must get inside the story and live with the story, in a sense becoming part of he community. This also allows you to know when not to be pointing your camera, when it would not be appropriate. There are times I do not make the picture, out of respect for the people and the moment.

With this Salgado draws a Bell curve on a pad of paper. The bottom of the near curve is where you — the photographer — approach and first enter a given situation. Here on the street you may be using a longish lens. Then you make your introductions. You explain yourself and most importantly, get permission.

At first the shooting can be very difficult, a steep, slow trudge up the curve. But after a few days or a week, as people become accustomed to you and your camera, you climb the curve more steadily. As you get deeper into the story your lens gets shorter. The pictures get better. When you approach the apex of the curve, there is less gravity working against you. The people have accepted you and dropped their defenses. The story enters its climax stage at the top of the curve and you are now using your shortest lens and making your best pictures. Inevitably you begin to sense a natural drop off; the story winds down. Traversing down the other side of the curve is a bit like cuddling and having a cigarette after sex. Gradually, and as gracefully as possible then, you extricate yourself from the bed of the story, giving your thanks and saying your goodbyes, while your lens (and here we must depart from the sex analogy) is once again getting longer.

Galeano: Salgado photographs people. Casual photographers photograph phantoms… Consumer-society photographers approach but do not enter. In hurried visits to scenes of despair or violence, they climb out of the plane or helicopter, press the shutter release, explode the flash: they shoot and run. They have looked without seeing and their images say nothing.

We spend a fair amount of time discussing the “framing” of a documentary project. In other words, know what you want to do, what your project is going to be about, and that your reasons for doing it are very important to you. If they are not, the difficulties of any given situation may overcome your dedication to it, and your work will reflect it.

Do as much research as you can. Wherever possible, develop contacts for your introductions ahead of time. Again, know the heart of the story you plan to tell with your photographs. Of course you cannot know the specifics; these will take care of themselves. And of course, things are never as you expect them on the ground, so you must also be nimble and prepared to make adjustments. Keep your eyes and your mind open, but at the same time stay focused on the main threads of your story. Otherwise you may think things are going well, only to return home and discover that somewhere along the way you lost your story, and are left with only a few nice pictures.

Fred Ritchin talks about some lesser-known aspects of Salgado. About how they worked together on a project to eliminate polio worldwide, which has been very successful if not 100 percent yet. He mentions how Salgado donates time and money to Medicins Sans Frontiers (MSF) and other groups helping the developing world. How he has rehabilitated rainforest in the Amazon where he grew up. How his current project, Genesis, is a risk and a departure from his previous work, and that he is learning a new medium format camera specifically for it.

The genesis of Genesis was Migrations, or rather the despair he felt at the he end of the project. He saw so much destruction of the environment, so much greed leading to human displacement and intractable poverty in the second and third worlds that his faith in humanity was badly waning. He wanted to address the reasons for this loss of faith in a way that would help to restore it, both for him and others. Like all his other major works, this project will take several years; he estimates seven. It is these multi-year projects that set Salgado apart from other great documentary photographers.

Salgado: I conceived this project as a potential path towards humanity's rediscovery of itself in nature. I have named it Genesis because, as far as possible, I want to return to the beginnings of our planet: to the air, water and fire that gave birth to life; to the animal species that have resisted domestication and are still "wild"; to the remote tribes whose "primitive" way of life is largely untouched; and to surviving examples of the earliest forms of human settlement and organization. This voyage represents a form of planetary anthropology. Yet it is also designed to propose that this uncontaminated world must be preserved and, where possible, be expanded so that development is not automatically commensurate with destruction.

Our breakfast with Salgado is over before we know it, and it’s time for lunch without him. Fred will continue the workshop after the break. Outside, still in something of a daze of icon envy, I spot Sebastiao heading down the block and resist the urge to run after him. He is off across the bay where he will be giving a fund raising speech later that night. To think that the best "pure" documentary photographer on the planet still has to work at raising money for his projects is more than a bit daunting. Seven-year projects are not easily funded of course, but the price of his well-earned emancipation from assignment work pays for itself in many other ways. Most importantly, it gives him the freedom to express the world he sees to the world at large, to speak directly through his lens without having to endure a bad translation from some editor sitting behind a desk in New York or Paris. There will be plenty of that after the fact, when the photo-intellectuals swoop down to feed and regurgitate to the public what they are so often incapable of fully digesting for themselves.