Shutter Release, January 2004

Diane Arbus (1923-1971) was a gifted portrait photographer who achieved fame

and some notoriety from her images of people who were emotionally or physically

aggrieved. Her subjects included awkward adolescents, tattooed roughnecks, sex orgies,

and persons she called “freaks” in a matter-of-fact way without deprecation. She lived

and worked in New York City, venturing to the toughest neighborhoods. Perhaps her

most famous image is of a giant (a man about 8 feet tall) stooping beside his parents

little more than half his height. The very tall man looks a bit frightening, and all have a

startled, almost pained expression on their faces.

In her time, Arbus was controversial and disliked by many critics. After her

death—sadly, she took her own life—her work was figuratively placed on the shelf, as if

an interesting curiosity of the past. In October 2003, her photography resurfaced with a

bang. An extensive exhibition, Diane Arbus Revelations, opened at the San Francisco

Museum of Modern Art; it will visit several US and European cities in 2004. Random

House has published a voluminous collection of these images under the same title. A

second show featuring her work, Diane Arbus: Family Albums, opened in December

and will run through March in Boston and New York City; a book is also available. The

New York Times and Aperture magazines devoted cover issues to Arbus as well. A

volley of reviews has followed. As a result, Diane Arbus and her work have become all

the rage in the world of art critique.

An Ethical Perspective

Behind the buzz of the retrospectives is a question: Was Arbus judged too

harshly in the past? The discussion centers on the motivation and merits of her focus on

people from whom most of us would avert our gaze—either they would be unpleasant to

see, or we would not want to embarrass them by our staring. An issue of ethics is

involved. While no one I’ve read has put it this starkly, the root question could be

expressed as:

Is it wrong to seek out and photograph people at their worst, when the apparent

motives are a compulsion to capture images of the down-and-out, and in the process

make a name for oneself and earn a living or profit?

Arbus’s Skills: Penetrating Portraiture and Access

Straightaway, Arbus deserves at least two honorable mentions. First, she was a

skilled portraitist. Using natural light, Arbus had an intuitive flair for drawing out and

illustrating the character of her subjects through the classical portraiture technique of

subtle differential shading of the sides of the face. And her images unfailingly show

great detail, often in difficult lighting situations and for the most part without graininess.

Second, and crucial to what she achieved, Arbus worked wonders in gaining

access. Access is among the least mentioned or discussed aspects of photography, but it

is vital to the success of most photographers. The majority of beautiful images require

the photographer to identify and locate the subjects, and “be there” fully sanctioned. This

is especially true (and occasionally downright risky) in people photography. Of course,

an established reputation or clientele make it easier in some circumstances, but it’s a long

haul.

It was in attaining access that Arbus demonstrated amazing skills. Her

photographs of people who would not normally want to be photographed were not candid

or taken on the fly or sly with telephoto lenses. Arbus sought out and persuaded her

subjects to pose.

Commentaries

The new exhibitions and books about Diane Arbus and her photography have

stimulated a number of reviews that touch on the ethical question of taking photographs

of the embarrassed, the downtrodden, the variants. . .

In Behind the Cruelly Probing Lens (Financial Times, 12/13/03), Richard

McClure writes: “Whereas once (Arbus) stood accused of voyeurism and prurient

curiosity, she is now painted as a kindred spirit to the misfits and outsiders she commonly

depicted. Far from seeming exploitive or demeaning, her pictures have come to be read

as metaphors for her own suffering; a cumulative self-portrait of a troubled mind.”

Following this, without directly faulting Arbus, McClure proceeds to debunk, by

way of examples, the notion that she harbored inherent good will or empathy for her

subjects. He writes of her disappointment, while visiting London in search of photo

opportunities, at not finding suitable subjects, and quotes her complaint: “Nobody seems

miserable, drunk, crippled, mad or desperate. I finally found a few vulgar things in the

suburbs, but nothing sordid yet.”

McClure’s clincher concerns Arbus’s famous image of the giant stooping over his

parents. His manner appears not quite human; all look nearly shell-shocked. McClure

informs us that the San Francisco exhibit includes a contact sheet with other images of

that shooting session. All the images show parents and child at ease and demonstrating a

natural fondness and affection for each other. Arbus did not publish these, selecting

instead the one image that appears to have been a fluke—as can occur when people are

frozen in motion—that shows the subjects at their worst.

In Good Pictures (New York Review of Books, January 15, 2004), Janet Malcolm

provides a more detailed, in-depth biographical study. After all the quotes, reminiscences

and opinions are digested, it appears that Malcolm considers Arbus an exceptional

photographer who produced memorable images. And that whatever her character and

motivation—on which the record, by my reading, is indicated as mixed—Arbus’s

photography served a purpose in society as well as her own mind, if only to get people to

look at a dimension of reality normally avoided.

Malcolm emphasizes that Arbus usually took her portraits against as plain a

background as possible—a demanding but ultimately rewarding technique. She stresses

that Arbus did not photograph her subjects without their permission.

Yet Malcolm initially quotes Jed Perl, writing in the New Republic, who

described Arbus as “one of those devious bohemians who celebrate other people’s

eccentricities and are all the while aggrandizing their own narcissistically pessimistic

view of the world.” This view is not directly contradicted, but is tempered by quotes and

reminiscences that suggest Arbus may have had good intent despite a cynicism about life.

Arbus is herself quoted in a style that could best be described as bohemian (and at worst,

early adolescent):

“Freaks was a thing I photographed a lot. . . There’s a quality of legend about

freaks. Like a person in a fairy tale who stops you and demands that you answer a riddle.

Most people go through life dreading they’ll have a traumatic experience. Freaks were

born with their trauma. They've already passed their test in life. They're aristocrats."

In the cover story, In Communion With the Outsider—What Diane Arbus

Was Shooting For (New York Times Magazine, September 14, 2003), Arthur Lebow

ventures to speculate on her mental state. On the basis of extensive interviews with

Arbus’s contemporaries as well as her writings, he concludes that Arbus enjoyed and was

not depressed by her photography of the down-and-out. She would be concerned,

however, about not having captured subjects truthfully (i.e., not portraying them as they

were). Lebow also suggests that Arbus’s suicide was related to events in her personal life

rather than her photography. Interestingly, the previously unpublished images

accompanying the article are of people from the mainstream—albeit anxious or

embarrassed at the moment—rather than from the margins of society. It turns out that

Arbus photographed more of conventional New York society than had been realized.

In a review, Looking Again Through Dark, Avid Lens of Diane Arbus

(Washington Times, January 4, 2004), Alexander Eliot provides a highly informative and

down-to-earth commentary with minimal abstraction. Eliot initially focuses on the

images—not the photographer—in the Diane Arbus Revelations book. He observes that

taken as a whole, the photographs comprise a finely crafted, eloquent story of the human

condition, or at least an important but rarely viewed side of it. Eliot writes, “To the dull

or hasty glance, her photographic ‘preserves’ often appear ugly or shocking, or both at

once. Yet they are indeed beautiful. . .as a variegated cast of brave souls. . .” (italics

added).

With regard to Arbus’s situation, Eliot is quite to the point:

“She was a true artist in the highest sense. In order to pursue her destiny, Diane required

a little money, and a little fame—but that’s the only reason she sought them. And her

few successes, in the practical sense, were more or less obliterated by successive riptides

of defeat. Most of the magazine editors for whom she worked exploited Diane, paying

rock-bottom fees, and even declining to reimburse her painfully modest expenses. As a

fragile, female free-lancer who was totally unequipped for, and unaccustomed to, the

rude, rough-and-tumble of professional existence, she suffered severe, humiliating

attrition throughout the last, best years of her career. Something soon upset the delicate

balance that made Diane’s intimate and yet cruel art worth living to create. What was it?

That’s not for me to guess. . .”

As to her motivation, Eliot quotes Arbus: “I truly believe there are things which

nobody would see unless I photographed them.”

Thank you, Mr. Eliot.

skip to main |

skip to sidebar

I have been thinking of why I love photography, it comes down to something I have labeled "The Three Joys"

1) Creativity

The first joy is simply creating the work. Everything about the making of photographs I love. The initial ideas, the writing on the blog, the preparation of equipment, the research into my subjects, figuring out what I want to communicate. The camera tech stuff like composition, lens selection, cameras, figuring exposure, taking the shot etc. The post darkroom work where you swim with your prints bringing them slowly to life, creating something powerful and beautiful. I love it all.

It is so powerful a thing, you have a idea in your mind, there is nothing else, then YOU make it, you create it, it's fricking awesome stuff.

2) The People

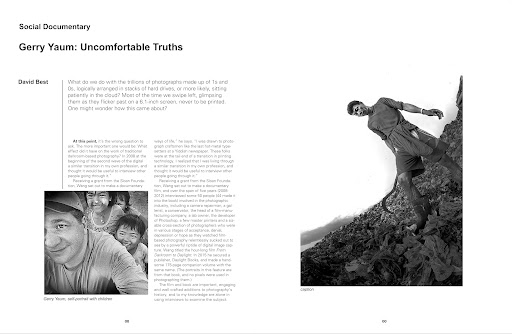

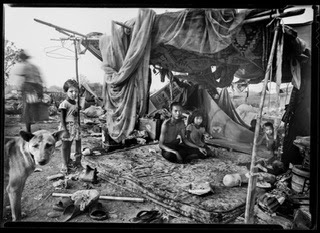

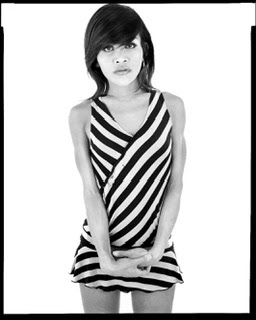

The second joy is that photography has allowed me a way into so many peoples lives, so many different worlds. I get to meet people of all types, speak to them, eat with them, cry and laugh with them. For a while I get to live their existence to be them if you will.

I get to be a child in a slum in Bangkok or a drug addict in a ghetto in Oakland. I get to be a ladyboy sex worker in Pattaya or a man dying of cancer in Canada. Of course I am not really those people but I get a true flavor for those worlds, those experiences, the good and the bad, the ugly and the beautiful, the joy and the sadness.

With photography I get a chance to live outside of the same same everyday meat and potato lives many of my friends and family live. Because I use a camera and make pictures all the doors to a wonderful life experience are open to me, photography is a window into everything!

3) The Photograph

The third joy is about the feeling you get when you accomplish your goals, when you see your final print in the developer, fix or hanging in a gallery. There is a special emotion there, a true satisfied happiness, something so uniquely rewarding. In the darkroom sometimes when I see the finished photo for the first time as it lays in the fixer tray I will let out hoops of joy. I will scream and shout. It is quite a spectacle! It's just the sheer high of that moment bursting out, the YES moment. When the photo is right and you see it for the first time it's the best feeling in the world, better than anything I have ever felt, the high of highs!!

"Ain't Photography Grand!"

"Ain't Photography Grand!!"

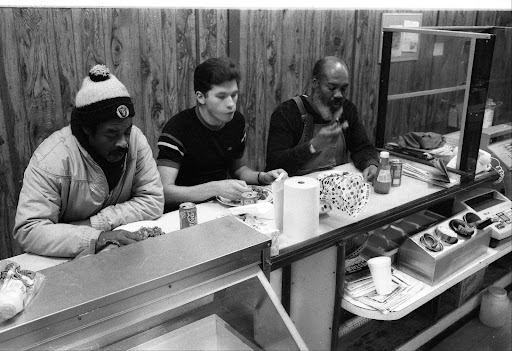

Social Documentary Photography for a Better World!

Search This Blog

Contact Gerry Yaum

contact@gerryyaum.net

Gerry Yaum Interview, FRAMES PHOTOGRAPHY MAGAZINE YouTube Channel

"Black & White" Photography Magazine, Issue #160

BLACK &WHITE Magazine, Layout Feature

CENTRE for BRITISH DOCUMENTARY PHOTOGRAPHY, CBDP

St. Albert Gazette MY FATHERS LAST DAYS Story

Me, W. Eugene Smith, Sebastiao Salgado, Lewis Hine and Walker Evans! :) NOT!!!

LUNCHBOX Radio Interview FOR UNB EXHIBITIONS

MONEY EARNED TO HELP THE PEOPLE IN THE PICTURES

Money that will be used to directly help the people in our two photography projects, THE FAMILIES OF THE DUM and THE PEOPLE WHO LIVE UNDER THE FREEWAY $6334.67 ($6000 earned when 6 prints were added to the UNB permanent collection).

GOFUNDME, FAMILES/FREEWAY

Trying to raise $2000 to help the people under the freeway, and the families of the dump. TOTAL RAISED SO FAR = $325 —->$314.67 (after GOFUNDME fees).

UNIVERSITY OF NEW BRUNSWICK EXHIBITIONS VIDEO

Analog Forever Magazine

Vernon Morning Star Newspaper Story

2022 "Families of the Dump"/The People Who Live Under The Freeway Donation Buys

Total donation money spent for the 2022 trip to the Mae Sot dump (THE FAMILIES OF THE DUMP), Bangkok's Klong Toey Slum (THE PEOPLE WHO LIVE UNDER THE FREEWAY). Money spent on "The Families of the Dump" = $571.17 CAD (14982 Thai Baht) Money spent on "The People Who Live Under The Freeway = $144 CAD (3849 Thai Baht) General cases where money was spent to help others in need $15 CAD (401baht)

(Thai Currency) or

CAD

"Families of the Dump" Donation Total

$4420.02 CAD

GERRY YAUM: YouTube Video PHOTOGRAPHY CHANNEL

THE GOAL

To create photographs that speak to the universality, the commonality and the shared humanity of all peoples, regardless of country, race, culture or language.

TRANSLATE YAUM'S PHOTO DIARY INTO YOUR LANGUAGE

Quote: Robert F. Kennedy

“The purpose of life is to contribute in some way to making things better.”

Quote: Nelson Mandela

"As long as poverty, injustice and gross inequality persist in our world, none of us can truly rest."

Quote: Weegee (Authur Fellig)

"Be original and develop your own style, but don't forget above anything and everything else...be human...think...feel. When you find yourself beginning to feel a bond between yourself and the people you photograph, when you laugh and cry with their laughter and tears, you will know your on the right track....Good luck."

Blog Archive

-

▼

2008

(236)

-

▼

July

(44)

- 2 More Ladyboys Photographed

- Bee Lady Sex Worker

- Simple Pleasures

- Quote: From the Book " Ladyboys the Secret World o...

- Current Portrait Count

- Mat and Dao

- Good Band

- Insulting Ladyboys

- Wednesday July 30

- Running Out of Days

- I---

- Nit

- Ladyboys Are Lining Up for Photo Sessions

- Tun

- Old Man With Thai Woman

- Goy and Oy

- Language Skills

- A Much Better Night

- Battery Charger Repaired

- Finding Faces Difficult

- Oyster Boy

- Another Good Photo Day

- The Cremation 2

- A Good Photo Day

- The Scene is Tiring

- 2nd night of photos

- Sick

- Danger

- Buddhist Funerals

- King

- Will Start Photographing Again Tonight

- The Cremation

- Unlucky Start

- Making Photos Day 1

- In Thailand

- Going Back

- Packing Film

- Quote: Edward Burtynsky, Photographer

- Quote: Diane Arbus

- Quote: Sid Grossman, Photographer

- Diane Arbus Revisited

- Wrestling with Diane Arbus

- Quote: Mildred Friedman, Writer and Curator

- Gallery Talk from the book Diane Arbus Revelations

-

▼

July

(44)

Total Pageviews

The Three Joys Of Photography

The Three Joys

1) Creativity

The first joy is simply creating the work. Everything about the making of photographs I love. The initial ideas, the writing on the blog, the preparation of equipment, the research into my subjects, figuring out what I want to communicate. The camera tech stuff like composition, lens selection, cameras, figuring exposure, taking the shot etc. The post darkroom work where you swim with your prints bringing them slowly to life, creating something powerful and beautiful. I love it all.

It is so powerful a thing, you have a idea in your mind, there is nothing else, then YOU make it, you create it, it's fricking awesome stuff.

2) The People

The second joy is that photography has allowed me a way into so many peoples lives, so many different worlds. I get to meet people of all types, speak to them, eat with them, cry and laugh with them. For a while I get to live their existence to be them if you will.

I get to be a child in a slum in Bangkok or a drug addict in a ghetto in Oakland. I get to be a ladyboy sex worker in Pattaya or a man dying of cancer in Canada. Of course I am not really those people but I get a true flavor for those worlds, those experiences, the good and the bad, the ugly and the beautiful, the joy and the sadness.

With photography I get a chance to live outside of the same same everyday meat and potato lives many of my friends and family live. Because I use a camera and make pictures all the doors to a wonderful life experience are open to me, photography is a window into everything!

3) The Photograph

The third joy is about the feeling you get when you accomplish your goals, when you see your final print in the developer, fix or hanging in a gallery. There is a special emotion there, a true satisfied happiness, something so uniquely rewarding. In the darkroom sometimes when I see the finished photo for the first time as it lays in the fixer tray I will let out hoops of joy. I will scream and shout. It is quite a spectacle! It's just the sheer high of that moment bursting out, the YES moment. When the photo is right and you see it for the first time it's the best feeling in the world, better than anything I have ever felt, the high of highs!!

"Ain't Photography Grand!"

Contact Gerry

- Gerry Yaum

- Edmonton, Alberta, Canada

- Email Gerry: gerryyaum@gmail.com

"Can a photograph stop a war? Can it save a life? Can it lead to understanding, inspire someone to help, provide comfort and open the door to compassion?

Hope that it can.

Pray that it can."

Hope that it can.

Pray that it can."