'Bhutan, the Sacred Within'

By KAREN ROSENBERG

Published: December 21, 2007

“Traveling many years, I have not yet seen a place as peaceful as Bhutan, or a place affecting such peacefulness within myself,” the photographer Kenro Izu writes. “If there is a place indeed named Utopia, this place may come the closest to it.” Mr. Izu has been taking photographs of sacred places since the late 1970s, but Bhutan, a Buddhist country of about 670,000 people nestled in the Himalayas, has become his personal Shangri-La.

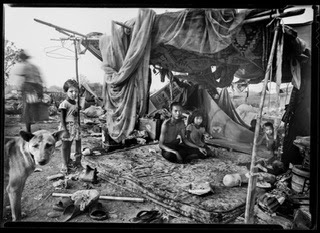

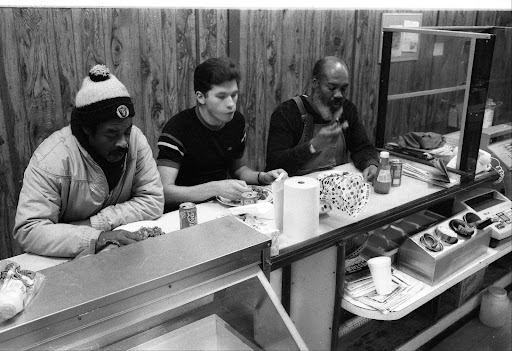

Life in Bhutan The black-and-white portraits and landscapes in “Bhutan, the Sacred Within: Photographs by Kenro Izu,” taken over the past five years, fall somewhere between photojournalism and pictorialism. Mr. Izu has not only made an earnest attempt to document the rarefied air of the Himalayas and the spiritual intensity of the Bhutanese; he has also enhanced them through a sensual printing process.

As Carleton Watkins and other early photographers of the American West did in their day, Mr. Izu contends with cumbersome equipment: a custom-made 300-pound camera that he brings on steep treks through the Himalayas. Later he makes contact prints (direct prints processed without enlargement) from 14-by-20-inch negatives, and then brushes on a coat of carbon pigment or platinum or palladium. The results have a satiny richness that somehow seems ephemeral, like unfixed charcoal.

Mr. Izu’s earlier photographs of the Himalayas were displayed in the Rubin Museum’s basement gallery in 2004, when the building first opened. On this occasion his work has been elevated to the museum’s third floor, where it is displayed against chocolate-brown walls alongside his hand-scripted travelogues, in his sometimes idiosyncratic English, and a small selection of Bhutanese art from the museum’s collection.

The images are also collected in an accompanying book, “Kenro Izu: Bhutan” (Nazraeli Press). Additional prints of Bhutan can be seen in “Kenro Izu: Stillness” at the Howard Greenberg Gallery, along with Mr. Izu’s Edward Weston-like still lifes of calla lilies and earlier photographs of spiritual architecture in India, Cambodia and elsewhere.

Perhaps in keeping with Buddhist philosophy, the exhibition at the Rubin (where galleries are organized around a large spiral staircase) does not have a specific entry point. The landscapes are a good place to begin.

The most prominent, an immense vista with Bhutan’s nearly 24,000-foot-high Mount Jomolhari, shows the ruins of a fortress silhouetted against blindingly white peaks. A striated gray sky is the only clue to the film’s long exposure time. The altitude is palpable. “I felt I captured the sacred mountain’s form in a radiant halo of light,” Mr. Izu writes.

A similarly scaled triptych presents a panoramic view of Taksang Monastery, a temple that disappears and reappears in the shifting clouds, like Brigadoon. It occupies a vertiginous spot “on the side of a precipice where the holy Padmasambhava is believed to have arrived astride a tigress,” Mr. Izu writes, referring to a revered eighth-century Buddhist mystic. Other landscapes show fluttering prayer flags reduced through long exposure times to indistinct smudges of gray.

In a series of portraits of monks and monks-in-training, Mr. Izu savors the elaborate masks and costumes worn by the Bhutanese. One mask has deeply carved wrinkles and trails white facial hair; another has vampiric fangs and a crown of five miniature skulls. The intricacy and variety of these ritual costumes are compelling, all the more so in the photographs that reveal bits of the wearer’s face and body. One boy, holding a mask with antlers, is clad in a robe and Western high-top sneakers.

Mr. Izu has taken many photographs of Bhutanese children, some more sentimental than others. A few of these images, like a shot of two toddlers holding hands and gazing over their shoulders at the camera, bear comparison to works by Henri Cartier-Bresson (also an admirer of Buddhism).

The child who seems to have made the strongest impression on Mr. Izu is a boy said to be the reincarnation of Guru Rimpoche (another name for Padmasambhava, who brought Buddhism to Bhutan and Tibet). The boy, who looks unusually self-possessed for his age, appears in two photos taken in a Paro monastery. In one of them, he tucks his hand into the folds of his robe in a Napoleonic pose.

“He stood in front of my camera, with an authority, unlike an ordinary child,” Mr. Izu writes. “The transparent eyes of a little Rimpoche seem questioning of my spiritual values as he gazed through the lens.”

Mr. Izu’s travelogue conveys a similar sense of awe mixed with self-doubt, particularly when he writes about the process of photographing the landscape. He also writes of his ambivalence about Bhutan’s tentative embrace of democracy (currently a monarchy, the country’s first democratic election is to be held in 2008):

“Seemingly, an existence of the precious culture in the edge of Himalayan itself is the fantasy of the 21st century, and I can’t help having a fear of its delicate fragility, which may easily dissolve into surrounding enormous clouds and fogs.”