Photography—Not Pictorial

Edward Weston, Camera Craft, Vol. 37, No. 7, pp. 313-20, 1930

"Art is an interpreter of the inexpressible, and therefore it seems a folly to try to convey its meaning afresh by means of words." This thought from Goethe is so true to me, that I hesitate before adding more words to the volumes both written and spoken by eager partisans—or politicians. I have always held that there is too much talk about art—not enough work. The worker will not have time to talk, to theorize—he will learn by doing.

But I have started with art as subject matter, though I have been asked to write my viewpoint on "Pictorial Photography." Are they, or can they be analogous? I would say, "Let the pedants decide that!" And yet—that word "Pictorial" irritates me: as I understand the making of pictures. Have we not had enough picture making—more or less refined "Calendar Art" by hundreds of thousands of painters and etchers? Photography following this line can only be a poor imitation of already bad art. Great painters—and I have had fortunate contacts with several of the greatest in this country, or in the world—are keenly interested in, and have deep respect for photography when it is photography both in technique and viewpoint, when it does something they cannot do; they only have contempt, and rightly so, when it is an imitation painting. And that is the trouble with most photography—just witness ninety per cent of the prints in innumerable salons—work done by those who if they had no camera would be third rate, or worse, painters. No photographer can equal emotionally nor aesthetically the work of a fine painter, both having the same end in view—that is, the painter's viewpoint. Nor can the painter begin to equal the photographer in his particular field.

The camera then, used as a means of expression, must have inherent qualities either different or greater than those of any other medium, otherwise, it has no value at all, except for commerce, science, or as a weekend hobby for weary businessmen—which would be fine if they did not expose their results to the public as art!

William Blake wrote: "Man is led to believe a lie, when he sees with, not through the eye." And the camera—the lens—can do that very thing—enable one to see through the eye, augmenting the eye, seeing more than the eye sees, exaggerating details, recording surfaces, textures that the human hand could not render with the most skill and labor. Indeed what painter would want to—his work would become niggling, petty, tight! But in a photograph this way of seeing is legitimate, logical.

So the camera for me is best in close up, taking advantage of this lens power: recording with its one searching eye the very quintessence of the thing itself rather than a mood of that thing—for instance, the object transformed for the moment by charming, unusual, even theatrical, but always transitory light effects. Instead, the physical quality of things can be rendered with utmost exactness: stone is hard, bark is rough, flesh is alive, or they can be made harder, rougher, or more alive if desired. In a word, let us have photographic beauty!

Is it art—can it be? Who knows or cares! It is a vital new way of seeing, it belongs to our day and age, its possibilities have only been touched upon. So why bother about art—a word so abused it is almost obsolete. But for the sake of discussion, the difference between good and bad art lies in the minds that created, rather than in skill of hands: a fine technician may be a very bad artist, but a fine artist usually makes himself a fine technician to better express his thought. And the camera not only sees differently with each worker using it, but sees differently than the eyes see: it must, with its single eye of varying focal lengths.

I cannot help feeling—and others have too—that certain great painters of the past actually had photographic eyes—born in this age they might well have used the camera. For instance, Velazquez. Diego Rivera wrote of him: "The talent of Velazquez manifesting itself in coincidence with the image of the physical world, his genius would have led him to select the technique most adequate for the purpose: that is to say, photography."

And there is Vincent Van Gogh who wrote "A feeling for things in themselves is much more important than a sense of the pictorial." Living today he might not use a camera, but he surely would be interested in some present day photographs.

Photography has or will eventually, negate much painting—for which the painter should be deeply grateful; relieving him, as it were, from certain public demands: representation, objective seeing. Rivera, I overheard in a heated discussion one day at an exhibit of photographs in Mexico: "I would rather have one of these photographs than any realistic painting: such work makes realistic painting superfluous."

For those who have been interested enough to follow me so far I will explain my way of working. With over twenty years of experience, I never try to plan in advance. Though I may from experience know about what I can do with a certain subject, my own eyes are no more than scouts on a preliminary search, for the camera's eye may entirely change my original idea, even switch me to different subject matter. So I start out with my mind as free from an image as the silver film on which I am to record, and I hope as sensitive. Then indeed putting one's head under the focusing cloth is a thrill, just as exciting to me today as it was when I started as a boy. To pivot the camera slowly around watching the image change on the ground glass is a revelation, one becomes a discoverer, seeing a new world through the lens. And finally the complete idea is there, and completely revealed. One must feel definitely, fully, before the exposure. My finished print is there on the ground glass, with all its values, in exact proportions. The final result in my work is fixed forever with the shutter's release. Finishing, developing, and printing is no more than a careful carrying on of the image seen on the ground glass. No after consideration such as enlarging portions, nor changing values—and of course no retouching—can make up for a negative exposed without a complete realization at the time of the exposure.

Photography is too honest a medium, direct and uncompromising, to allow of subterfuge. One notes in a flash a posed gesture or assumed expression in portraiture—or in landscape, a clear day made into a foggy one by use of a diffused lens, or an underexposed sunset labeled "Moonlight"!

The direct approach to photography is the difficult one, because one must be a technical master as well as master of one's mind. Clear thinking and quick decisions are necessary: technique must be a part of one, as automatic as breathing, and such technique is difficult. I can, and have taught a child of seven to expose, develop, and print creditably in a few weeks, thanks to the great manufacturers who have so simplified and made fool-proof the various steps in picture making: which accounts for the flood of bad photography by those who think it an easy way to "express" themselves. But it is not easy! —not easy to see on the ground glass the finished print, to mentally carry that image on through the various processes of finishing to a final result, and with reasonable surety that the result will be exactly what one originally saw and felt. I say mentally carry the image to stress the point that no manual interference is allowed, nor desired in my way of working. Photography so considered becomes a medium requiring the greatest accuracy, and surest judgment. The painter can, if he wishes, change his original conception as he works, at least every detail is not conceived beforehand, but the photographer must see the veriest detail which can never be changed. Often a moment or a second or the fraction of a second of time must be captured without hesitancy. What a fine training in seeing, in accuracy, for anyone—for a child especially. I have started two of my own boys in photography and expect to with the other two: not wanting nor even hoping that they will become photographers, but to give them a valuable aid in whatever line of work they may choose to follow.

I may be writing for a very few persons, maybe only one, no more is to be expected. To the few, or the one, I would finally say, learn to think photographically and not in terms of other media, then you will have something to say which has not been already said. Realize the limitations as well as possibilities of photography. The artist unrestrained by a form, within which he must confine his original emotion, could not create. The photographer must work out his problem, restricted by the size of his camera, the focal length of his lens, the certain grade of dry plate or film, and the printing process he is using: within these limitations enough can be said, more than has been so far—for photography is young.

Actually I am not arguing for my way. An argument indicates a set frame of mind by those who participate, and to remain fluid, ready to change, indeed eager to, is the only way to grow. Personal growth is all that counts. Not, am I greater than another, but am I greater than I was last year or yesterday. Each of us is in a certain stage of development and it would be a drab world if we all thought alike.

Some there are who will remember my work of fifteen years ago, or less, and some will like my past better than my present. To the latter I have not much to say; they are still in a world where lovely poetic impressions are more important than the aesthetic beauty of the thing itself.

Seeing Photographically

Edward Weston, The Complete Photographer, Vol. 9, No. 49, pp. 3200-3206, 1943

Each medium of expression imposes its own limitations on the artist —limitations inherent in the tools, materials, or processes he employs. In the older art forms these natural confines are so well established they are taken for granted. We select music or dancing, sculpture or writing because we feel that within the frame of that particular medium we can best express whatever it is we have to say.

The Photo-Painting Standard

Photography, although it has passed its hundredth birthday, has yet to attain such familiarization. In order to understand why this is so, we must examine briefly the historical background of this youngest of the graphic arts. Because the early photographers who sought to produce creative work had no tradition to guide them, they soon began to borrow a ready-made one from the painters. The conviction grew that photography was just a new kind of painting, and its exponents attempted by every means possible to make the camera produce painter-like results. This misconception was responsible for a great many horrors perpetrated in the name of art, from allegorical costume pieces to dizzying out of focus blurs.

But these alone would not have sufficed to set back the photographic clock. The real harm lay in the fact that the false standard became firmly established, so that the goal of artistic endeavor became photo-painting rather than photography. The approach adopted was so at variance with the real nature of the medium employed that each basic improvement in the process became just one more obstacle for the photo-painters to overcome. Thus the influence of the painters' tradition delayed recognition of the real creative field photography had provided. Those who should have been most concerned with discovering and exploiting the new pictorial resources were ignoring them entirely, and in their preoccupation with producing pseudo-paintings, departing more and more radically from all photographic values.

As a consequence, when we attempt to assemble the best work of the past, we most often choose examples from the work of those who were not primarily concerned with aesthetics. It is in commercial portraits from the daguerreotype era, records of the Civil War, documents of the American frontier, the work of amateurs and professionals who practiced photography for its own sake without troubling over whether or not it was art, that we find photographs that will still stand with the best of contemporary work.

But in spite of such evidence that can now be appraised with a calm, historical eye, the approach to creative work in photography today is frequently just as muddled as it was eighty years ago, and the painters' tradition still persists, as witness the use of texture screens, handwork on negatives, and ready-made rules of composition. People who wouldn't think of taking a sieve to the well to draw water fail to see the folly in taking a camera to make a painting.

Behind the photo-painter's approach lay the fixed idea that a straight photograph was purely the product of a machine and therefore not art. He developed special techniques to combat the mechanical nature of his process. In his system the negative was taken as a point of departure—a first rough impression to be "improved" by hand until the last traces of its unartistic origin had disappeared.

Perhaps if singers banded together in sufficient numbers, they could convince musicians that the sounds they produced through their machines could not be art because of the essentially mechanical nature of their instruments. Then the musician, profiting by the example of the photo-painter, would have his playing recorded on special discs so that he could unscramble and rescramble the sounds until he had transformed the product of a good musical instrument into a poor imitation of the human voice!

To understand why such an approach is incompatible with the logic of the medium, we must recognize the two basic factors in the photographic process that set it apart from the other graphic arts: the nature of the recording process and the nature of the image.

Nature of the Recording Process

Among all the arts photography is unique by reason of its instantaneous recording process. The sculptor, the architect, the composer all have the possibility of making changes in, or additions to, their original plans while their work is in the process of execution. A composer may build up a symphony over a long period of time; a painter may spend a lifetime working on one picture and still not consider it finished. But the photographer's recording process cannot be drawn out. Within its brief duration, no stopping or changing or reconsidering is possible. When he uncovers his lens every detail within its field of vision is registered in far less time than it takes for his own eyes to transmit a similar copy of the scene to his brain.

Nature of the Image

The image that is thus swiftly recorded possesses certain qualities that at once distinguish it as photographic. First there is the amazing precision of definition, especially in the recording of fine detail; and second, there is the unbroken sequence of infinitely subtle gradations from black to white. These two characteristics constitute the trademark of the photograph; they pertain to the mechanics of the process and cannot be duplicated by any work of the human hand.

The photographic image partakes more of the nature of a mosaic than of a drawing or painting. It contains no lines in the painter's sense, but is entirely made up of tiny particles. The extreme fineness of these particles gives a special tension to the image, and when that tension is destroyed—by the intrusion of handwork, by too great enlargement, by printing on a rough surface, etc.—the integrity of the photograph is destroyed.

Finally, the image is characterized by lucidity and brilliance of tone, qualities which cannot be retained if prints are made on dull-surface papers. Only a smooth, light-giving surface can reproduce satisfactorily the brilliant clarity of the photographic image.

Recording the Image

It is these two properties that determine the basic procedure in the photographer's approach. Since the recording process is instantaneous, and the nature of the image such that it cannot survive corrective handwork, it is obvious that the finished print must be created in full before the film is exposed. Until the photographer has learned to visualize his final result in advance, and to predetermine the procedures necessary to carry out that visualization, his finished work (if it be photography at all) will represent a series of lucky—or unlucky—mechanical accidents.

Hence the photographer's most important and likewise most difficult task is not learning to manage his camera, or to develop, or to print. It is learning to see photographically—that is, learning to see his subject matter in terms of the capacities of his tools and processes, so that he can instantaneously translate the elements and values in a scene before him into the photograph he wants to make. The photopainters used to contend that photography could never be an art because there was in the process no means for controlling the result. Actually, the problem of learning to see photographically would be simplified if there were fewer means of control than there are.

By varying the position of his camera, his camera angle, or the focal length of his lens, the photographer can achieve an infinite number of varied compositions with a single, stationary subject. By changing the light on the subject, or by using a color filter, any or all of the values in the subject can be altered. By varying the length of exposure, the kind of emulsion, the method of developing, the photographer can vary the registering of relative values in the negative. And the relative values as registered in the negative can be further modified by allowing more or less light to affect certain parts of the image in printing. Thus, within the limits of his medium, without resorting to any method of control that is not photographic (i.e., of an optical or chemical nature), the photographer can depart from literal recording to whatever extent he chooses.

This very richness of control facilities often acts as a barrier to creative work. The fact is that relatively few photographers ever master their medium. Instead they allow the medium to master them and go on an endless squirrel cage chase from new lens to new paper to new developer to new gadget, never staying with one piece of equipment long enough to learn its full capacities, becoming lost in a maze of technical information that is of little or no use since they don't know what to do with it.

Only long experience will enable the photographer to subordinate technical considerations to pictorial aims, but the task can be made immeasurably easier by selecting the simplest possible equipment and procedures and staying with them. Learning to see in terms of the field of one lens, the scale of one film and one paper, will accomplish a good deal more than gathering a smattering of knowledge about several different sets of tools.

The photographer must learn from the outset to regard his process as a whole. He should not be concerned with the "right exposure," the "perfect negative," etc. Such notions are mere products of advertising mythology. Rather he must learn the kind of negative necessary to produce a given kind of print, and then the kind of exposure and development necessary to produce that negative. When he knows how these needs are fulfilled for one kind of print, he must learn how to vary the process to produce other kinds of prints. Further he must learn to translate colors into their monochrome values, and learn to judge the strength and quality of light. With practice this kind of knowledge becomes intuitive; the photographer learns to see a scene or object in terms of his finished print without having to give conscious thought to the steps that will be necessary to carry it out.

Subject Matter and Composition

So far we have been considering the mechanics of photographic seeing. Now let us see how this camera-vision applies to the fields of subject matter and composition. No sharp line can be drawn between the subject matter appropriate to photography and that more suitable to the other graphic arts. However, it is possible, on the basis of an examination of past work and our knowledge of the special properties of the medium, to suggest certain fields of endeavor that will most reward the photographer, and to indicate others that he will do well to avoid.

Even if produced with the finest photographic technique, the work of the photo-painters referred to could not have been successful. Photography is basically too honest a medium for recording superficial aspects of a subject. It searches out the actor behind the make-up and exposes the contrived, the trivial, the artificial, for what they really are. But the camera's innate honesty can hardly be considered a limitation of the medium, since it bars only that kind of subject matter that properly belongs to the painter. On the other hand it provides the photographer with a means of looking deeply into the nature of

things, and presenting his subjects in terms of their basic reality. It enables him to reveal the essence of what lies before his lens with such clear insight that the beholder may find the recreated image more real and comprehensible than the actual object.

It is unfortunate, to say the least, that the tremendous capacity photography has for revealing new things in new ways should be overlooked or ignored by the majority of its exponents—but such is the case. Today the waning influence of the painter's tradition, has been replaced by what we may call Salon Psychology, a force that is exercising the same restraint over photographic progress by establishing false standards and discouraging any symptoms of original creative vision.

Today's photographer need not necessarily make his picture resemble a wash drawing in order to have it admitted as art, but he must abide by "the rules of composition." That is the contemporary nostrum. Now to consult rules of composition before making a picture is a little like consulting the law of gravitation before going for a walk. Such rules and laws are deduced from the accomplished fact; they are the products of reflection and after-examination, and are in no way a part of the creative impetus. When subject matter is forced to fit into preconceived patterns, there can be no freshness of vision. Following rules of composition can only lead to a tedious repetition of pictorial cliches.

Good composition is only the strongest way of seeing the subject. It cannot be taught because, like all creative effort, it is a matter of personal growth. In common with other artists the photographer wants his finished print to convey to others his own response to his subject. In the fulfillment of this aim, his greatest asset is the directness of the process he employs. But this advantage can only be retained if he simplifies his equipment and technique to the minimum necessary, and keeps his approach free from all formula, art-dogma, rules, and taboos. Only then can he be free to put his photographic sight to use in discovering and revealing the nature of the world he lives in.

skip to main |

skip to sidebar

I have been thinking of why I love photography, it comes down to something I have labeled "The Three Joys"

1) Creativity

The first joy is simply creating the work. Everything about the making of photographs I love. The initial ideas, the writing on the blog, the preparation of equipment, the research into my subjects, figuring out what I want to communicate. The camera tech stuff like composition, lens selection, cameras, figuring exposure, taking the shot etc. The post darkroom work where you swim with your prints bringing them slowly to life, creating something powerful and beautiful. I love it all.

It is so powerful a thing, you have a idea in your mind, there is nothing else, then YOU make it, you create it, it's fricking awesome stuff.

2) The People

The second joy is that photography has allowed me a way into so many peoples lives, so many different worlds. I get to meet people of all types, speak to them, eat with them, cry and laugh with them. For a while I get to live their existence to be them if you will.

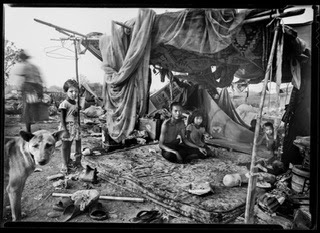

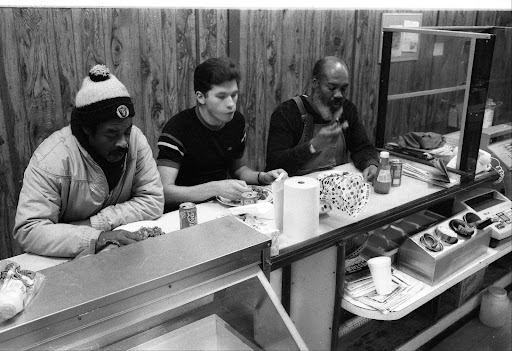

I get to be a child in a slum in Bangkok or a drug addict in a ghetto in Oakland. I get to be a ladyboy sex worker in Pattaya or a man dying of cancer in Canada. Of course I am not really those people but I get a true flavor for those worlds, those experiences, the good and the bad, the ugly and the beautiful, the joy and the sadness.

With photography I get a chance to live outside of the same same everyday meat and potato lives many of my friends and family live. Because I use a camera and make pictures all the doors to a wonderful life experience are open to me, photography is a window into everything!

3) The Photograph

The third joy is about the feeling you get when you accomplish your goals, when you see your final print in the developer, fix or hanging in a gallery. There is a special emotion there, a true satisfied happiness, something so uniquely rewarding. In the darkroom sometimes when I see the finished photo for the first time as it lays in the fixer tray I will let out hoops of joy. I will scream and shout. It is quite a spectacle! It's just the sheer high of that moment bursting out, the YES moment. When the photo is right and you see it for the first time it's the best feeling in the world, better than anything I have ever felt, the high of highs!!

"Ain't Photography Grand!"

"Ain't Photography Grand!!"

Social Documentary Photography for a Better World!

Search This Blog

Contact Gerry Yaum

contact@gerryyaum.net

Gerry Yaum Interview, FRAMES PHOTOGRAPHY MAGAZINE YouTube Channel

"Black & White" Photography Magazine, Issue #160

BLACK &WHITE Magazine, Layout Feature

CENTRE for BRITISH DOCUMENTARY PHOTOGRAPHY, CBDP

St. Albert Gazette MY FATHERS LAST DAYS Story

Me, W. Eugene Smith, Sebastiao Salgado, Lewis Hine and Walker Evans! :) NOT!!!

LUNCHBOX Radio Interview FOR UNB EXHIBITIONS

MONEY EARNED TO HELP THE PEOPLE IN THE PICTURES

Money that will be used to directly help the people in our two photography projects, THE FAMILIES OF THE DUM and THE PEOPLE WHO LIVE UNDER THE FREEWAY $6334.67 ($6000 earned when 6 prints were added to the UNB permanent collection).

GOFUNDME, FAMILES/FREEWAY

Trying to raise $2000 to help the people under the freeway, and the families of the dump. TOTAL RAISED SO FAR = $325 —->$314.67 (after GOFUNDME fees).

UNIVERSITY OF NEW BRUNSWICK EXHIBITIONS VIDEO

Analog Forever Magazine

Vernon Morning Star Newspaper Story

2022 "Families of the Dump"/The People Who Live Under The Freeway Donation Buys

Total donation money spent for the 2022 trip to the Mae Sot dump (THE FAMILIES OF THE DUMP), Bangkok's Klong Toey Slum (THE PEOPLE WHO LIVE UNDER THE FREEWAY). Money spent on "The Families of the Dump" = $571.17 CAD (14982 Thai Baht) Money spent on "The People Who Live Under The Freeway = $144 CAD (3849 Thai Baht) General cases where money was spent to help others in need $15 CAD (401baht)

(Thai Currency) or

CAD

"Families of the Dump" Donation Total

$4420.02 CAD

GERRY YAUM: YouTube Video PHOTOGRAPHY CHANNEL

THE GOAL

To create photographs that speak to the universality, the commonality and the shared humanity of all peoples, regardless of country, race, culture or language.

TRANSLATE YAUM'S PHOTO DIARY INTO YOUR LANGUAGE

Quote: Robert F. Kennedy

“The purpose of life is to contribute in some way to making things better.”

Quote: Nelson Mandela

"As long as poverty, injustice and gross inequality persist in our world, none of us can truly rest."

Quote: Weegee (Authur Fellig)

"Be original and develop your own style, but don't forget above anything and everything else...be human...think...feel. When you find yourself beginning to feel a bond between yourself and the people you photograph, when you laugh and cry with their laughter and tears, you will know your on the right track....Good luck."

Blog Archive

-

▼

2011

(552)

-

▼

May

(23)

- Quote: Martin Luther King Jr.

- Quote: Consuelo Kanaga (Photographer)

- Wish I Was Making Photographs

- Would Rather Be Invisible

- I Have Some Good News And Bad News For You

- I Feel It

- Final Klong Toey 35mm Shots

- More More Klong Toey 35mm Slum Photos

- Hard Edged 35mm Photo Story

- More Bangkok Klong Toey Slum 35mm Scans

- "Faded Lives", Details

- Edward Weston: Seeing Photographically

- Eugene W. Smith Moment

- Deleting History

- Some More Scans From The Last Thai Trip

- Color Printing Started

- Frames Cut

- Running Out Of Time

- Partial Failure

- Nice Meeting

- Framing This Week

- Working On My Spotting

- Time To Leave The Club World?

-

▼

May

(23)

Total Pageviews

The Three Joys Of Photography

The Three Joys

1) Creativity

The first joy is simply creating the work. Everything about the making of photographs I love. The initial ideas, the writing on the blog, the preparation of equipment, the research into my subjects, figuring out what I want to communicate. The camera tech stuff like composition, lens selection, cameras, figuring exposure, taking the shot etc. The post darkroom work where you swim with your prints bringing them slowly to life, creating something powerful and beautiful. I love it all.

It is so powerful a thing, you have a idea in your mind, there is nothing else, then YOU make it, you create it, it's fricking awesome stuff.

2) The People

The second joy is that photography has allowed me a way into so many peoples lives, so many different worlds. I get to meet people of all types, speak to them, eat with them, cry and laugh with them. For a while I get to live their existence to be them if you will.

I get to be a child in a slum in Bangkok or a drug addict in a ghetto in Oakland. I get to be a ladyboy sex worker in Pattaya or a man dying of cancer in Canada. Of course I am not really those people but I get a true flavor for those worlds, those experiences, the good and the bad, the ugly and the beautiful, the joy and the sadness.

With photography I get a chance to live outside of the same same everyday meat and potato lives many of my friends and family live. Because I use a camera and make pictures all the doors to a wonderful life experience are open to me, photography is a window into everything!

3) The Photograph

The third joy is about the feeling you get when you accomplish your goals, when you see your final print in the developer, fix or hanging in a gallery. There is a special emotion there, a true satisfied happiness, something so uniquely rewarding. In the darkroom sometimes when I see the finished photo for the first time as it lays in the fixer tray I will let out hoops of joy. I will scream and shout. It is quite a spectacle! It's just the sheer high of that moment bursting out, the YES moment. When the photo is right and you see it for the first time it's the best feeling in the world, better than anything I have ever felt, the high of highs!!

"Ain't Photography Grand!"

Contact Gerry

- Gerry Yaum

- Edmonton, Alberta, Canada

- Email Gerry: gerryyaum@gmail.com

"Can a photograph stop a war? Can it save a life? Can it lead to understanding, inspire someone to help, provide comfort and open the door to compassion?

Hope that it can.

Pray that it can."

Hope that it can.

Pray that it can."