September 14, 2003

By Arthur Lubow

'Giving a camera to Diane Arbus is like giving a hand grenade to a baby,'' Norman Mailer said after seeing how she had captured him, leaning back in a velvet armchair with his legs splayed cockily. The quip was funny, but a little off base. A camera for Arbus was like a latchkey. With one around her neck, she could open almost any door. Fearless, tenacious, vulnerable -- the combination conquered resistance. In an eye-opening sequence in ''Revelations,'' the compendious new book that is being published in tandem with a full-scale retrospective at the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, you discover with a start the behind-the-scenes drama that produced her famous photograph of ''A Naked Man Being a Woman.'' As her title indicates, it is a portrait of a young man standing naked in his apartment, genitals tucked out of sight, in a Venus-on-the-half-shell pose. First she photographed him as a bouffant-haired young matron on a park bench; then at home in a bra and half slip; unwigged and unclothed a few moments later, with legs demurely crossed; up posing for the prized shot; and finally, as a seemingly ordinary fellow back on a park bench. Somehow, she had persuaded him to take her home and expose a secret life. It's what she did again and again. ''She got herself to go up to people on the street and ask if she could photograph them,'' recalls her former husband, Allan Arbus. ''One thing she often said was, 'I'm just practicing.''' He chuckles. ''And indeed, I guess she was.''

During her lifetime, Arbus was lionized, but she was also lambasted for being exploitative. Her suicide in 1971 seemed to corroborate the caricature of her as a freaky ghoul. The critic Susan Sontag divined that Arbus photographed ''people who are pathetic, pitiable, as well as repulsive,'' from a vantage point ''based on distance, on privilege, on a feeling that what the viewer is asked to look at is really other.'' Patricia Bosworth's biography in 1984 took the suicide as an emblem of the life and told a lurid tale that is neatly summarized by the tag line on the paperback edition: ''HER CAMERA WAS THE WINDOW TO A TORTURED SOUL.'' In The New York Review of Books, Jonathan Lieberson eviscerated Bosworth's book but also deprecated Arbus's pictures as ''mannered, static snapshots'' that were ''chaste, icy, stylized.'' Chaste, icy, stylized? Arbus's friend Richard Avedon, maybe. Not Diane Arbus.

Doon Arbus was 26 when Diane died. As the older daughter of a divorced mother, she took on the responsibility of managing the estate. Her response to the critics was to clamp the spigot shut. Arbus's letters, journals and diaries could not be examined. Anyone wishing to reproduce Arbus photographs would have to submit the book or article for Doon's vetting; any museum contemplating a retrospective had to enlist her active collaboration. In almost all cases, permission was denied. Unsurprisingly, critics and scholars fumed. As Anthony W. Lee, the co-author of a new academic treatise, ''Diane Arbus: Family Albums,'' puts it in an acid footnote, ''Those familiar with the writings on Arbus's photographs will recognize a common thread that joins them all, which this essay also shares: nearly all are published without the benefit of reproductions of some of her most famous work.'' That work now appeared in three handsome, meticulous monographs, which over the last three decades Doon has compiled and released.

So it comes as a shock to see -- in the first full-scale museum retrospective since 1972 and in the book -- that Diane Arbus at long last is presented whole. Together with the pictures that have become icons (the Jewish giant and his bewildered parents, the disturbingly different identical twins, the in-process transvestite in hair curlers, etc.), there are many of her photographs that have never been seen (or even, in some cases, printed). Better still, there is a rich assortment of extracts from her letters and journals that reveal her to be a quirky, funny, first-rate writer, an extraordinarily loving mother and an empathetic observer of her photographic subjects. More than 30 years after her death, a new portrait is emerging of one of the most powerful American artists of the 20th century, in the style that she favored. Uncropped.

Allan, who is now a trim and graceful white-haired man of 85, gave Diane her first camera soon after they married in 1941. She was 18, and they had met five years earlier, when he started working at Russek's department store on Fifth Avenue in Manhattan, the fur and clothing emporium founded by her grandfather and run by her father, David Nemerov. Diane was the second of three children (her older brother, Howard, became a prize-winning poet). She was named for a character in a play her mother enjoyed; as with her fictional namesake, it was pronounced ''Dee-ann.'' During Diane's childhood, the Nemerovs lived in large apartments on Central Park West and on Park Avenue. ''The family fortune always seemed to me humiliating,'' she told the journalist Studs Terkel. ''It was like being a princess in some loathsome movie'' set in ''some kind of Transylvanian obscure Middle European country.'' The public rooms were filled with reproduction French furniture in slipcovers. In the Nemerovs' home life, as in their ritzy clothing store, everything was for show.

Diane attended the Ethical Culture Fieldston School in the leafy Riverdale section of the Bronx, where the student body was composed largely of the children of affluent, liberal Jews. In art class, her renderings stood apart. ''She would look at a model and draw what none of us saw,'' recalls her classmate, the screenwriter Stewart Stern. Yet she mistrusted her facility with a paintbrush. ''As soon as she finished something, she'd show it and they'd say, 'Oh, Diane, it's marvelous, it's marvelous,''' Allan recounts. Diane told Terkel that praise of that sort ''made me feel shaky.'' Her father enlisted the Russek's fashion illustrator to give her lessons, but Diane lost interest in painting, perhaps because it was easy for her. ''I had a sense that if I were terrific at it, it wasn't worth doing, and I had no real sense of wanting to do it,'' she said.

She felt otherwise about the Graflex, a smaller version of the classic newsman's camera, that she received from Allan. Photography suited her. She had a sharp eye. ''We once visited a cousin of mine,'' Allan recalls. ''He had a large bookcase, which extended -- '' He indicates a span of 8 or 10 feet. ''We sat on a couch opposite the bookcase. Some weeks later, we visited him again, and Diane said, 'Oh, you have a new book.''' The newlyweds would study photographs in galleries, especially Alfred Stieglitz's American Place, and in the Museum of Modern Art. The Park Avenue apartment building in which Diane's parents lived had a darkroom for the use of tenants. The young Arbuses appropriated it.

David Nemerov, who was wondering how his son-in-law intended to earn a living, happily hired the couple to do advertising shoots for Russek's. ''We were living, breathing photography at every moment,'' Allan says. ''This was a way to get paid for it.'' Although he and Diane admired the photojournalism of Henri Cartier-Bresson, the heyday of the pictorial newsmagazine was about to fade before the allure of television, and the excitement -- along with the opportunity -- was in fashion magazines. The Second World War delayed until 1946 the debut of their fashion photography studio, which operated under the joint credit ''Diane & Allan Arbus.'' Diane came up with the ideas; Allan set up the lights and camera, clicked the shutter, developed the film and printed the proofs. The business was a success but unremittingly stressful. ''We never felt satisfied,'' Allan explains. ''There was that awful seesaw. When Diane felt O.K., I would be in the dumps, and when I would be exhilarated, she would be depressed.'' In retrospect, he says he thinks it was a mistake to demand a concept for each shoot rather than simply photograph models in front of white no-seam paper, as Avedon did in Harper's Bazaar to great acclaim. ''I guess we figured if we photographed the way Dick did, it wouldn't come out,'' he says. ''We were afraid to try it. I remember one day Dick just popped into the studio. We were talking back and forth. I said, 'When we started in this, I thought it would be so easy.' He said, 'Isn't it?'''

In 1951, they closed down the studio and escaped to Europe with their 6-year-old daughter, Doon. (Their second child, Amy, would be born three years later.) But the respite lasted only a year. Once back, it was the same grind for four more years until, one night in 1956, Diane quit. ''I can't do it anymore,'' she told Allan unexpectedly one evening. Her voice rose an octave. ''I'm not going to do it anymore.'' Although unprepared, Allan understood. ''At a fashion sitting, I was the one operating the camera,'' he says. ''I was directing the models on what to do. And Diane would have to go in and pin the dress if it wasn't hanging right. It was demeaning to her. It was a repulsive role.'' At first he was terrified of operating without her. ''But it came out all right,'' he says. ''In some ways, it was easier to work, because I didn't have that load of Diane's dissatisfaction to deal with.''

Soon after Arbus's death, the art director Marvin Israel -- who was her lover, colleague, critic and goad -- told a television journalist: ''It could be argued that for Diane the most valuable thing wasn't the photograph itself, the art object; it was the event, the experience. . . . The photograph is like her trophy -- it's what she received as the reward for this adventure.'' Today, when you shuffle through the lifeless photos by imitators in the Arbus idiom, you are reminded of how much time Arbus spent with so many of her subjects and of how fascinated she was by their lives. She invested the energy in them that a painter like Lucian Freud or Francis Bacon would devote to repeated portrait sittings; but unlike Freud or Bacon, who chose their intimates as their subjects, Arbus picked strangers and, through her infectious empathy, was able to transform these subjects into intimates. ''She was an emissary from the world of feeling,'' says the photographer Joel Meyerowitz. ''People opened up to her in an emotional way, and they yielded their mystery.'' Without sentimentalizing them or ignoring their failings, she liked and admired her freaks. She first met Eddie Carmel, the Jewish giant, almost a decade before she took her extraordinary photograph of him with his parents. You feel that had she never gotten the picture, Arbus still would have considered the time with Carmel well spent.

Robert Brown, a neighbor and friend who often breakfasted with the Arbuses when they lived on East 72nd, recalls a Sunday morning, probably in 1957, when Allan showed Diane a newspaper item that he knew would interest her: the circus was coming to town. The troupe would be debarking from a train early the next morning and parading to Madison Square Garden. ''Let's go!'' Diane said. Allan was too busy, but Brown, who is an actor, accompanied her to the parade and then drove her to Madison Square Garden. Coming to pick her up three hours later, Brown asked the backstage doorman where she was. ''Oh, the photographer?'' the man answered. ''She never got very far.'' He pointed. She was sitting on the floor with the midgets. ''I don't think she was snapping,'' Brown says. ''She was getting involved.''

Arbus trawled the city, getting deeply involved with the people who caught her eye: the sideshow performers at Hubert's Dime Museum and Flea Circus, the cross-dressers at Club 82, the moonstruck visionaries with handmade helmets and crackpot theories, the magicians and fortunetellers and self-proclaimed prophets. But she also pursued more ''ordinary'' types -- the swimmers at Coney Island, the strollers down Fifth Avenue, the people on benches in Central Park. At first, she was shy about getting too close. Sometimes she would catch her quarry unawares, from a distance, and then crop the image to give a close-up effect. But she wasn't happy doing that. ''We were very against cropping,'' Allan says. She wanted to capture her subjects whole and unaltered, before adding them to her ''butterfly collection.''

Many of her pictures from the 50's are grainy, in the style of Cartier-Bresson, Robert Frank and other documentary photographers of the time. ''The reduced tonal scale makes it seem like a copy of a copy, like an old record that's faded and a lot of the information is gone,'' says John Szarkowski, curator emeritus of photography at the Museum of Modern Art. ''Which is fine for a certain kind of description, where you know you're not getting everything.'' In the late 50's, however, something mysterious transformed Arbus's work. ''I don't think there is any development,'' Szarkowski says. ''It happened all at once. Basically, it was like St. Paul on the road to Damascus.'' Allan is more specific: ''That was Lisette. Three sessions and Diane was a photographer.''

Diane took her first course with Lisette Model in 1956. Earlier she had studied briefly with Berenice Abbott and Alexey Brodovitch, but Model had a far greater impact on her artistically and personally. ''Model was able to instill in Arbus a self-confidence of approach and engagement that really released her,'' says Peter C. Bunnell, curator emeritus of photography at Princeton University. ''Arbus in her own personality was rather shy. Not what Lisette was, in a European tradition, an independent, aggressive woman.'' Model's great influence on Arbus came through their conversations about the art of photography. ''After three months, her style was there,'' Model told the writer Phillip Lopate. ''First only grainy and two-tone. Then perfection.'' Arbus, shortly before her death, told her own class of students, ''It was my teacher, Lisette Model, who finally made it clear to me that the more specific you are, the more general it'll be.''

The Arbuses' professional split was followed in 1959 by a personal one. Diane and the girls moved to a converted stable in the West Village. It was a subtle separation. Allan maintained the fashion photography business under the joint credit. He continued to test Diane's new cameras and to have his assistants develop her film. She printed her photos in his darkroom. He managed their joint finances, and he often came for Sunday breakfast. However, despite the persistence of their bond, the separation and eventual divorce forced -- and liberated -- Diane to step out on her own. ''I always felt that it was our separation that made her a photographer,'' Allan says. ''I couldn't have stood for her going to the places she did. She'd go to bars on the Bowery and to people's houses. I would have been horrified.''

Certainly, Diane was traveling far from the white seamless world of fashion photography. Because so many of her subjects lived on the fringes of polite society, her pictures provoked a controversy that has yet to die down. Most people today who are familiar with the name ''Diane Arbus'' would probably identify her as ''the photographer of freaks.'' This stereotype insulates them from the power of the photographs. Portraits of sideshow freaks constitute a small portion of Arbus's output. On the other hand, it is true that she adored them. ''There's a quality of legend about freaks,'' she told a Newsweek reporter. ''Like a person in a fairy tale who stops you and demands that you answer a riddle.'' She said that she would ''much rather be a fan of freaks than of movie stars, because movie stars get bored with their fans, and freaks really love for someone to pay them honest attention.'' But the word ''freak'' is so vague and charged that it can be misleading. Arbus did not photograph people who were disfigured by calamity -- fire, toxic poisoning, war. She was not a photojournalist like W. Eugene Smith. She did not chase after victims. The pacifist Paul Salstrom once traveled with her to a motel that his aunt managed near Los Angeles. After the aunt agreed to be photographed, Salstrom inquired if Arbus would also like to photograph his uncle, but she declined. ''My uncle had a large growth on the back of his neck,'' Salstrom explains. ''She said, 'I'm not going to ask him, because I feel sorry for him.'''

Arbus regarded circus freaks as ''aristocrats'' and female impersonators as gender-barrier pioneers. To her, there was nothing pathetic or repulsive about them. One of her most famous pictures is ''A Young Brooklyn Family Going for a Sunday Outing, N.Y.C., 1966.'' With teased black hair and heavily outlined eyebrows, the woman is made up to look like Elizabeth Taylor, an aspiration that, inevitably, she has not quite achieved. Her arms are overburdened with a large pocketbook, a camera in its case, a leopard-patterned coat and a big baby girl, and although she is looking straight ahead, she seems preoccupied. Her baby's arms and face are extended forward, as is the honest, open gaze of her husband. The only off-kilter figure in this upstanding group is their son, a mentally retarded boy, his eyes, head and body all askew, his small hand held by his father. Unlike the mother, the father is grasping onto nothing else but his son, whose crooked body fills the gap between the parents. As another photo in ''Revelations'' establishes, Arbus spent some time in this family's home. She later wrote, ''They were undeniably close in a painful sort of way.''

Arbus's choice of subject matter was not especially novel. From the transvestites of Brassaï to the circus dwarf of Bruce Davidson, odd-looking and socially transgressive people have always attracted the attention of photographers. But even when those photographers took you backstage, you still felt that you were at a performance. Arbus went home with her subjects, literally and emotionally. That's why her portraits of a young man in hair curlers or a half-dressed dwarf in bed retain the power to shock. It's not the subjects that unnerve us: her photographs of a middle-class woman in pearls or a pair of twins with headbands can be just as startling. What shocks is the intimacy. ''I don't like to arrange things,'' she said. ''If I stand in front of something, instead of arranging it, I arrange myself.'' When she took a picture, she instinctively found the right place to stand. Her vantage point denied the viewer any protective distance.

Once she parachuted out of fashion photography, Arbus relied on magazine editors for assignments. Her empathetic curiosity and undivided focus -- ''whatever the moment presented, she was in it,'' says her friend Mary Sellers -- made her a remarkable reporter. On a trip Arbus took to Los Angeles in 1964, Robert Brown, who by then was living there, chauffeured her to Mae West's house on two successive days. When he picked her up the first night, she was bubbling with excitement. ''You know what we did most of the time?'' she told him. ''She's got a locked room with models in plaster of all the men she's had sex with -- of their erections.'' Reminiscing about her former lovers, West had waxed rhapsodic: ''Each one is different: the way they sigh, the way they moan, the way they move; even the feel of them, their flesh is just a little different. . . . There's a man for every mood.'' Arbus took it all down for the article she would write. She probably waited until the next day, by which point West would have been completely charmed and relaxed, to take the visual record of the septuagenarian sexpot -- in negligee, backlighted by the merciless Southern California sun. ''Mae West hated the pictures,'' Allan Arbus recalls. ''Because they were truthful.''

A waiflike figure with huge green eyes, a goofy grin and a girlish giggle, Arbus would roam the city, laden down with camera equipment. Her blend of whispery fragility and unstoppable tenacity was very seductive. ''She had this little squeaky voice, completely unarming because she was so childlike and her interest so genuine,'' says the photographer Larry Fink, who observed her working in New York parks. ''So she would hover there and smile and be a little embarrassed, with her Mamiyaflex going. She would wait for people to relax, or to get so tense that they would be the opposite of relaxed, with much the same effect.'' Sandra Reed, the albino sword swallower who is the subject of one of Arbus's most arresting late photographs, recalls Arbus, clad in denim, coming up to her before the circus opened. ''I thought it was someone wanting an autograph,'' Reed says. ''She would get a rapport going between you and her. She asked me how it was to travel around, places I'd seen, things I'd done. She was very relaxed, a very ordinary person. She talked to me about the sword-swallowing, how I did it. We talked for quite some time, an hour, maybe two. She asked me if I would mind to be in full costume, and I said, 'No problem.''' Reed performed her act, and Arbus photographed her. The shoot, Reed thinks, took about 45 minutes.

''People were interested in Diane, just as interested in her as she was in them,'' Szarkowski says. He first met Arbus late in 1962. He had recently succeeded Edward Steichen as director of photography at the Museum of Modern Art, and Arbus was picking up a portfolio of her work that she had dropped off for review. ''It was an accident,'' he says. ''I came out of my office, so my assistant introduced us somewhat embarrassedly. I liked her immediately. She was a person with a very lively intelligence. So the conversation went on, and it got to the point where she asked what I thought of the work.'' Arbus's portfolio consisted mostly of portraits of eccentric New Yorkers that she had done for Harper's Bazaar. Szarkowski remembers telling her: '''I don't find it quite right. It seems to me the photographs don't fit what your intention is.'''

They were grainy 35-millimeter pictures, the sort that photojournalists snapped on the fly. ''Technically, they looked a little bit like Robert Frank, not quite like Bill Klein,'' Szarkowski says. ''I said to her, 'It seems to me what you're interested in is much more permanent, ceremonial, eidetic.''' He then pointed to an anomalous photograph she had taken with a large Rolleiflex camera that produces a more finely detailed, square negative. '''That's what you're looking for; it's like Sander,''' Szarkowski recalls saying to her. ''Maybe it was my North Wisconsin accent. She said, 'Who's Sander?'''

Perhaps it was his twang, or maybe Arbus was momentarily distracted, because she certainly was familiar by then with the work of the great German photographer August Sander. Shrewd as Szarkowski was to recognize the affinity, Sander had been brought to her attention two years earlier by Marvin Israel, who would prove to be the most astute and important champion of Arbus's work. Israel, like Arbus, was a person who thrived on contradictions. He was raised in a well-off New York Jewish family (the money came from a women's-clothing business) but affected a down-at-the-heels bohemian style. A protégé of Alexey Brodovitch, who galvanized American magazine design with the electric energy of the Bauhaus and Russian Constructivism, Israel was art director of Seventeen in the late 50's and then himself became the art director of Brodovitch's baby, Harper's Bazaar. He worked in a dusty, cluttered three-floor studio in the cupola of a building on lower Fifth Avenue, amid the cacophony of birdcalls (a parrot and a caged crow being the loudest) and the barking of a vicious adopted stray mongrel, named Marvin. ''Shut up, Marvin,'' he would bark back.

In late November 1959, a few months after moving into the West Village carriage house, Arbus met Israel, and they became lovers. Their intense friendship and professional collaboration would continue until the end of her life.

Israel gave Arbus a portfolio of Sander photographs from a 1959 issue of the Swiss magazine Du, seeing immediately that Sander was the photographer whose ambition and perspicacity most resembled her own. Sander set himself a monumental task -- ''to see things as they are and not as they should or might be''; by so doing, he thought he could provide a ''physiognomic image of an age.'' In his Teutonic thoroughness and anthropological zeal, Sander was a creature of his place and time; as an artist, however, he transcends those categories. Sander was after clarity. He printed on the shiny smooth paper normally used for technical illustrations, and he ignored the introduction of panchromatic glass plates that would obscure blemishes. He typically spent an hour or more talking with his subject before taking the photograph, and whenever possible, he scheduled the sitting in the subject's home, not in a studio, to capture more of the truth.

In the next generation, Bernd and Hilla Becher took up Sander's typological mania and ran with it. What fascinated Arbus about Sander was the psychological inquiry, which she adopted and pushed as far as she could. Arbus photographed many of the same subjects as Sander (carnival performers, midgets, women in slinky dresses, blind people, twins). Comparing their work is instructive. For example, Sander's portrait of fraternal twins, from 1925, shows a timid, eager-to-please girl and a dour, conventional little boy; you can see, as in embryo, the roles in society that they are preparing to play. In contrast, there is nothing sociological about Arbus's 1967 portrait of identical twin girls in Roselle, N.J. Instead, she has taken a kind of psychological X-ray. The girl on the right smiles angelically and trustingly. The one on the left is slightly off: her eyes are misaligned, her mouth is suspiciously pursed, her stockings are bunched at the knees, even the bobby pins on her white headband have slipped below her eyes. Wearing identical frocks, the girls are standing so close that they seem to be joined in one body, two aspects of the same soul. ''What's left after what one isn't is taken away is what one is,'' Arbus wrote in a notebook in 1959. That aphorism could be the caption to this picture.

Marvin Israel said that when he was at Bazaar, he wanted to assign Arbus to photograph every person in the world. In the early heady days of their affair, when she was peppering Israel with almost daily postcards, Arbus once wrote him that ''everyone today looked remarkable just like out of August Sander pictures, so absolute and immutable down to the last button, feather, tassel or stripe. All odd and splendid as freaks and nobody able to see himself, all of us victims of the especial shape we come in.'' By the time Arbus picked up a camera, the termite-riddled social order of Sander's day had crumbled. She was fascinated by people who were visibly creating their own identities -- cross-dressers, nudists, sideshow performers, tattooed men, the nouveau riche, the movie-star fans -- and by those who were trapped in a uniform that no longer provided any security or comfort. Arbus's friend Adrian Allen, who began her career as an assistant to the legendary Brodovitch, recalls going through the layout of the posthumous monograph that Doon and Israel put together and seeing with shock the image of a woman she had known, seated on a park bench. In her three-strand necklace and helmetlike bouffant hairdo, Arbus's subject seems riven by secret hopelessness. ''I had never seen this woman look like that before,'' Allen says. ''She was always laughing, smiling, covering up what was underneath.'' Somehow, like a dowser of despair, Arbus had picked up the signal of misery. Not long after the picture was taken, the woman in the bouffant hairdo committed suicide.

Because Arbus took her own life, many people assume that she was constantly grim. Actually, she was an enthusiastic woman with a highly honed sense of the absurd, who was afflicted by blasts of bleakness. ''She was a very lively person,'' Szarkowski says. ''She had a very vivacious mind. She was never a depressed person in my presence.'' Allan Arbus, who knew her as well as anyone did, saw a fuller picture. ''I was intensely aware of these violent changes of mood,'' he says. ''There were times when it was just awful, and there were times. . . . '' His expression mimics fizzy exhilaration. Diane preferred receiving confidences to giving them, one reason photography was her natural medium. ''She wanted to contend with something else, not express herself,'' Doon says.

The relationship with Israel was painful for Arbus. Married to Margie Ponce Israel, a brilliant but emotionally troubled artist, he was not as reliably available or emotionally supportive as Arbus wished. ''Diane made no secret of the fact that she was waiting and waiting for Marvin's attention,'' says Elisabeth Sussman, co-curator of the show at the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, who has gone through Arbus's journals, letters and date books. Arbus did not talk to most of her friends about Israel. Unusually, the artist Mary Frank knew them both independently. ''A desire to be cared for is a very human instinct,'' Frank says. ''Marvin could not have given Diane that feeling. He was a very complicated person, and interested in his own powers. He was capable of kindness, but then there was this explosive aspect.'' Frank says that she saw Arbus despondent a couple of times, and ''it definitely had to do with Marvin.'' Where Allan gave Diane technical advice and emotional bolstering, Israel excited her to take on new projects and challenges. ''He was always interested in artists pushing as hard as they could toward their own obsessions or perversities,'' says the writer Lawrence Shainberg, who was a close friend.

Like Arbus, Israel loved to explore the seamier precincts of New York. They didn't have to go far. Forty-Second Street was very different then: ''everyone winking and nudging and raising their eyebrows and running their hands through their marcelled hair and I saw one of your seeing blind men and a man like you have told me about with the pale ruined face-that-isn't-there and a thousand lone conspirators,'' Arbus wrote Israel. Some of those trophies appeared publicly when she agreed with much trepidation to be included, along with Lee Friedlander and Garry Winogrand, in an exhibition, ''New Documents,'' that opened at the Museum of Modern Art in February 1967. Like the contemporaneous ''New Journalists'' in Esquire and New York (Arbus worked for both magazines), the newfangled documentary photographers in this show made the seeing eye a part of the picture. To her relief, Arbus adored the way her work looked hanging in the museum galleries. ''I've been here as many times as I can get here -- I love it,'' she told a reporter. However, her ambivalence about presenting her photographs as art objects remained. In March 1969, in Midtown New York, Lee Witkin opened the first commercially viable gallery devoted to photography. Arbus agreed to let him display some of her pictures, but she declined his offer of a large exhibition. Although she accepted offers to lecture and sold prints to museums, she always voiced her doubts about whether she was ready for this attention.

In the months after the New Documents show, she bristled with new ideas. ''She would have 30 projects at once,'' Allan says. But then she would fall into funks that were harder and harder for her to pull out of. ''She was in so much pain, and really struggling with what the meaning of her life was,'' Mary Sellers says. ''I had never felt her to be as fragile and unsure.''

When the lease came up on the carriage house, Arbus was forced to move, in January 1968, to a less attractive apartment in the East Village. She had had a serious bout of hepatitis two years earlier; in 1968, she suffered a relapse. Maybe most unsettling to her was Allan's decision to move to Los Angeles in June 1969 to pursue an acting career. ''I guess it was oddly enough the finality of Allan leaving (for Calif.) that so shook me,'' she wrote to her friend Carlotta Marshall. ''He had been gone somewhat for a hundred years but suddenly it was no more pretending. This was it. . . . I am learning all over again it seems how to live, how to make a living, how to do what I want and what I don't, all sorts of commonsensical things I have tended to make a big deal about.'' One of the things that she had to learn was how to develop film, because Allan was closing his darkroom. Although she had always made her own prints, she relied on his assistants for processing film. ''It was hard for her to take over this part of photography,'' he says. The technical aspects never appealed to her. ''She was very funny about her cameras,'' he continues. ''If one didn't work, she would put it aside and then pick it up the next day to see if it had gotten better.'' Yet she knew precisely what look she was after, and she would improvise technically to achieve it. In 1965, she began printing her negatives with the black border exposed -- as if to emphasize both that this image was uncropped and thus unaltered, and also (sabotaging its pretensions to truth) that in the end it was only a photograph. ''For me the subject of the picture is always more important than the picture,'' she once said. ''And more complicated.''

In the last two years of her life, she was working on a project that delighted her deeply. Through a relative of Adrian Allen, she obtained permission to photograph at institutions for the severely retarded in New Jersey. These pictures, which Doon posthumously labeled the ''Untitled'' series, represent a sharp departure from Arbus's previous work. Combining flash unpredictably with daylight and catching her subjects on the move, she was relinquishing control and embracing the accidental. She wrote Allan that the photographs ''are very blurred and variable, but some are gorgeous. FINALLY what I've been searching for, and I seem to have discovered sunlight, late afternoon early winter sunlight. It's just marvelous. In general I seem to have perverted your brilliant technique all the way round, bending it over backward you might say till it's JUST like snapshots but better.'' In her notebook, she devoted five pages to individual descriptions of her retarded subjects. Writing to Amy, she explained: ''Some of them are so small that their shoulder would fit right under my arm and I would pat them and their head would fall on my chest. They are the strangest combination of grown-up and child I have ever seen. One lady kept saying over and over: 'I'm sorry, I'm sorry.' After a while one of the staff said, 'That's all right but don't do it again' and she quieted down. . . . I think you'd like them.''

Adrian Allen went to see the photographs in the Westbeth artist-housing complex in the West Village, which is where Arbus moved from East 10th Street in January 1970. ''The whole floor was filled with that project,'' Allen recalls. ''At first I found it kind of awful to look at these people. Then, as I started to look at the larger prints and found how the people connected with her -- they were the sort of people who couldn't connect with anybody, but that quality she had of getting people to let her in, even if they were mad or retarded -- in those pictures, I sensed her presence.'' Allen understood that Arbus's excitement arose from her attachment to her retarded subjects. ''She loved the photographs because they illustrated the connection.'' She had devoted so much energy to getting people to doff their masks. Now, with these mentally impaired people, she found a transparency of expression. Oddly, in many of her most famous photographs of them, they are wearing masks for Halloween.

Sometimes the work would buoy her spirits, but not for long. ''She was always, always both devoted to and loathing of photography,'' Mary Sellers says. ''She was always wondering not was it good enough, but was it true enough.''

In many of her late photographs, she returned to her early practice of capturing people who were unaware of her camera. But the effect was different now. She was a mature artist, and she could find the intimacy she wanted in unexpected ways. So that in ''A Woman Passing, N.Y.C., 1971,'' the determined hunch of the walk, the proudly chic uplift of the hat and the liver-spotted hand gripping the pocketbook make us feel we know this woman as well as if we had read a novel about her. As early as 1967, Diane wrote to Amy: ''I suddenly realized that when I photograph people I don't anymore want them to look at me. (I used nearly always to wait for them to look me in the eye but now it's as if I think I will see them more clearly if they are not watching me watching them.)''

One of the many misperceptions about Arbus is that her work, in its emotional toll and immersion in the ''dark side,'' contributed to a fatal despair. In fact, her work elated her. ''She made it seem like a lark,'' says Michael Flanagan, a friend of hers and Israel's, who worked for a time as Allan's assistant and developed her negatives. ''The pictures were sometimes dark and scary, but she was lighthearted, like it was an adventure for her.'' The doubts and depressions were triggered by other causes, sometimes by a sense of abandonment, at times by an internal biological flux she could neither understand nor control. ''I go up and down a lot,'' she wrote Carlotta Marshall in late 1968. ''Maybe I've always been like that. Partly what happens though is I get filled with energy and joy and I begin lots of things or think about what I want to do and get all breathless with excitement and then quite suddenly either through tiredness or a disappointment or something more mysterious the energy vanishes, leaving me harassed, swamped, distraught, frightened by the very things I thought I was so eager for! I'm sure this is quite classic.'' She went to visit Allan and his new wife, Mariclare Costello, in Los Angeles in the fall of 1970. He remembers that once, while driving in the car, she told him: ''I took a pill before we left and I feel much better. It's all chemical.''

Marshall saw her several times in mid-July 1971, on a visit to New York from Holland, where she now lived. At their last get-together, they stayed up late, talking. ''We talked about suicide and death, but we talked about everything,'' Marshall says. ''I just didn't pay special attention to the fact that she brought it up. It wasn't a morbid discussion.'' On July 26, when Marshall was on a ship heading back to Europe, Allan was acting in a movie in Santa Fe, Doon was working on a book in Paris, Amy was attending summer school in Massachusetts and Israel was weekending with his wife at Avedon's house on Fire Island, Arbus swallowed a number of barbiturates, climbed fully dressed into her bathtub and cut her wrists with a razor blade. Two days later, Israel went to her apartment and found the body.

Arbus was 48 when she died. In the autopsy report, the Medical Examiner's Office left this tantalizing observation: ''Diary suggestive of suicidal intent, taken on July 26th, noted.'' The on-the-scene medical investigator's report refers to a '''Last Supper' note,'' and Lawrence Shainberg, one of three friends whom Israel called to wait with him for the police to arrive, recalls seeing the words ''Last Supper'' written on a page of her open diary. What could she have meant? At the Last Supper, Jesus said that the wine and unleavened bread were his blood and body, containing eternal life -- a black-humor analogy for someone slashing her wrists and gulping fatal tablets. He also said that he would be betrayed by someone very close to him.

Did Arbus leave other clues in her date book? We don't know. The diary page for the 26th, and for the two pages following, have been neatly excised. ''I've stared at that book for I can't say how long,'' says Sussman, the co-curator. That Arbus took secrets with her to the grave is completely in character. She collected other people's mysteries and divulged few of her own. ''I never thought that I knew all her secrets,'' Allan says. (Asked if she knew all of his, he says, ''Probably.'') The diaries, notebooks and letters that are included in the museum retrospective and in ''Revelations'' enable us to come closer to seeing Arbus in the way that she saw her subjects -- with an unexpected, even unsettling, intimacy. Never for a second, however, do we feel that we have exhausted the mystery.

skip to main |

skip to sidebar

I have been thinking of why I love photography, it comes down to something I have labeled "The Three Joys"

1) Creativity

The first joy is simply creating the work. Everything about the making of photographs I love. The initial ideas, the writing on the blog, the preparation of equipment, the research into my subjects, figuring out what I want to communicate. The camera tech stuff like composition, lens selection, cameras, figuring exposure, taking the shot etc. The post darkroom work where you swim with your prints bringing them slowly to life, creating something powerful and beautiful. I love it all.

It is so powerful a thing, you have a idea in your mind, there is nothing else, then YOU make it, you create it, it's fricking awesome stuff.

2) The People

The second joy is that photography has allowed me a way into so many peoples lives, so many different worlds. I get to meet people of all types, speak to them, eat with them, cry and laugh with them. For a while I get to live their existence to be them if you will.

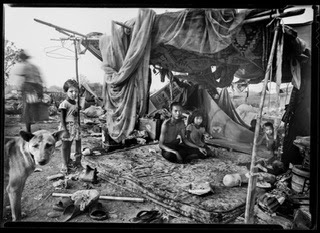

I get to be a child in a slum in Bangkok or a drug addict in a ghetto in Oakland. I get to be a ladyboy sex worker in Pattaya or a man dying of cancer in Canada. Of course I am not really those people but I get a true flavor for those worlds, those experiences, the good and the bad, the ugly and the beautiful, the joy and the sadness.

With photography I get a chance to live outside of the same same everyday meat and potato lives many of my friends and family live. Because I use a camera and make pictures all the doors to a wonderful life experience are open to me, photography is a window into everything!

3) The Photograph

The third joy is about the feeling you get when you accomplish your goals, when you see your final print in the developer, fix or hanging in a gallery. There is a special emotion there, a true satisfied happiness, something so uniquely rewarding. In the darkroom sometimes when I see the finished photo for the first time as it lays in the fixer tray I will let out hoops of joy. I will scream and shout. It is quite a spectacle! It's just the sheer high of that moment bursting out, the YES moment. When the photo is right and you see it for the first time it's the best feeling in the world, better than anything I have ever felt, the high of highs!!

"Ain't Photography Grand!"

"Ain't Photography Grand!!"

Social Documentary Photography for a Better World!

Search This Blog

Contact Gerry Yaum

contact@gerryyaum.net

Gerry Yaum Interview, FRAMES PHOTOGRAPHY MAGAZINE YouTube Channel

"Black & White" Photography Magazine, Issue #160

BLACK &WHITE Magazine, Layout Feature

CENTRE for BRITISH DOCUMENTARY PHOTOGRAPHY, CBDP

St. Albert Gazette MY FATHERS LAST DAYS Story

Me, W. Eugene Smith, Sebastiao Salgado, Lewis Hine and Walker Evans! :) NOT!!!

LUNCHBOX Radio Interview FOR UNB EXHIBITIONS

MONEY EARNED TO HELP THE PEOPLE IN THE PICTURES

Money that will be used to directly help the people in our two photography projects, THE FAMILIES OF THE DUM and THE PEOPLE WHO LIVE UNDER THE FREEWAY $6334.67 ($6000 earned when 6 prints were added to the UNB permanent collection).

GOFUNDME, FAMILES/FREEWAY

Trying to raise $2000 to help the people under the freeway, and the families of the dump. TOTAL RAISED SO FAR = $325 —->$314.67 (after GOFUNDME fees).

UNIVERSITY OF NEW BRUNSWICK EXHIBITIONS VIDEO

Analog Forever Magazine

Vernon Morning Star Newspaper Story

2022 "Families of the Dump"/The People Who Live Under The Freeway Donation Buys

Total donation money spent for the 2022 trip to the Mae Sot dump (THE FAMILIES OF THE DUMP), Bangkok's Klong Toey Slum (THE PEOPLE WHO LIVE UNDER THE FREEWAY). Money spent on "The Families of the Dump" = $571.17 CAD (14982 Thai Baht) Money spent on "The People Who Live Under The Freeway = $144 CAD (3849 Thai Baht) General cases where money was spent to help others in need $15 CAD (401baht)

(Thai Currency) or

CAD

"Families of the Dump" Donation Total

$4420.02 CAD

GERRY YAUM: YouTube Video PHOTOGRAPHY CHANNEL

THE GOAL

To create photographs that speak to the universality, the commonality and the shared humanity of all peoples, regardless of country, race, culture or language.

TRANSLATE YAUM'S PHOTO DIARY INTO YOUR LANGUAGE

Quote: Robert F. Kennedy

“The purpose of life is to contribute in some way to making things better.”

Quote: Nelson Mandela

"As long as poverty, injustice and gross inequality persist in our world, none of us can truly rest."

Quote: Weegee (Authur Fellig)

"Be original and develop your own style, but don't forget above anything and everything else...be human...think...feel. When you find yourself beginning to feel a bond between yourself and the people you photograph, when you laugh and cry with their laughter and tears, you will know your on the right track....Good luck."

Blog Archive

-

▼

2009

(254)

-

▼

June

(53)

- On to Other Countries?

- Two More Photo Sessions to Go

- Mod 23

- Nid 6 Years Later

- Long's Story

- A Room Full of Ladyboys

- Bla's Room

- Drunk

- Photographing Bla Again

- Nurse or Girlfriend??

- Bay

- Gerry Yaum Goes French

- Darkroom Fun Ahead

- Future Projects

- Ti, Sak and Jiab

- Drunks and Sex

- German chokes on dentures, dies in a Soi 6 bar

- Following Jock's Advice

- Da

- Boy Gogos

- Overheard Conversation

- Hair Cut

- Eli Expat

- Feeling Comfortable

- Rak and Gai

- Gop

- Rak

- Police Raids

- Da Strong Thai Lady

- R American Expat

- Sico

- Thai Massage

- Bla

- Noy and Nui

- Ladyboy Prejudice

- Thai Massage

- Social Deviants?

- Expat Quote

- Expat Quote

- 10 dollar Meal

- Speaking Thai Again

- Broken Ground Glass

- Walking the Scene, Tired

- Matt 26

- Joom 28

- 2 English Blokes

- Nit 50

- The Silent Dinner

- In Thai

- Randy

- Quote: Mary Seller friend of Diane Arbus

- Quotes: Diane Arbus

- Arbus Reconsidered

-

▼

June

(53)

Total Pageviews

The Three Joys Of Photography

The Three Joys

1) Creativity

The first joy is simply creating the work. Everything about the making of photographs I love. The initial ideas, the writing on the blog, the preparation of equipment, the research into my subjects, figuring out what I want to communicate. The camera tech stuff like composition, lens selection, cameras, figuring exposure, taking the shot etc. The post darkroom work where you swim with your prints bringing them slowly to life, creating something powerful and beautiful. I love it all.

It is so powerful a thing, you have a idea in your mind, there is nothing else, then YOU make it, you create it, it's fricking awesome stuff.

2) The People

The second joy is that photography has allowed me a way into so many peoples lives, so many different worlds. I get to meet people of all types, speak to them, eat with them, cry and laugh with them. For a while I get to live their existence to be them if you will.

I get to be a child in a slum in Bangkok or a drug addict in a ghetto in Oakland. I get to be a ladyboy sex worker in Pattaya or a man dying of cancer in Canada. Of course I am not really those people but I get a true flavor for those worlds, those experiences, the good and the bad, the ugly and the beautiful, the joy and the sadness.

With photography I get a chance to live outside of the same same everyday meat and potato lives many of my friends and family live. Because I use a camera and make pictures all the doors to a wonderful life experience are open to me, photography is a window into everything!

3) The Photograph

The third joy is about the feeling you get when you accomplish your goals, when you see your final print in the developer, fix or hanging in a gallery. There is a special emotion there, a true satisfied happiness, something so uniquely rewarding. In the darkroom sometimes when I see the finished photo for the first time as it lays in the fixer tray I will let out hoops of joy. I will scream and shout. It is quite a spectacle! It's just the sheer high of that moment bursting out, the YES moment. When the photo is right and you see it for the first time it's the best feeling in the world, better than anything I have ever felt, the high of highs!!

"Ain't Photography Grand!"

Contact Gerry

- Gerry Yaum

- Edmonton, Alberta, Canada

- Email Gerry: gerryyaum@gmail.com

"Can a photograph stop a war? Can it save a life? Can it lead to understanding, inspire someone to help, provide comfort and open the door to compassion?

Hope that it can.

Pray that it can."

Hope that it can.

Pray that it can."