By Greta Berman

As March is Women's History Month, I thought I would focus on an exhibition showing one woman's depiction of "the family." However, if you go to this show expecting to see warm and cuddly family albums of "normal" people, you will be in for a surprise.

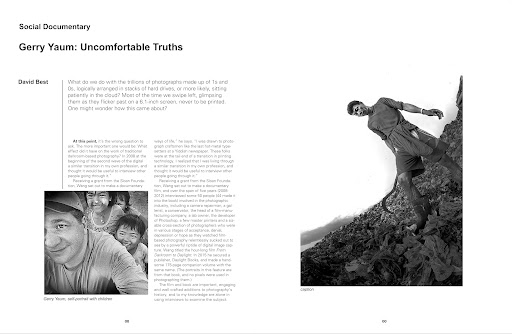

Jayne Mansfield Cimber-Ottaviano, actress, with her daughter Jayne Marie, thirteen, 1965 (Copyright © Estate of Diane Arbus, 1965. Esquire Collection, Spencer Museum of Art, the University of Kansas)

It has been said that the definition of "normal" is someone you don't know very well. But for Diane Arbus, this was particularly true. Using her camera as a tool, she probed beneath any veneer of "normalcy." Through her photography, she demonstrated her considered opinion: "I think all families are creepy in a way." In fact, she seemed to find most challenging those families held together by blood, marriage, and law, often portraying alternative "families" in a more sympathetic light. Three years before committing suicide in 1968, she wrote that she was compiling her photos into a "family album," likening it to a Noah's Ark, in which to preserve images of creatures soon to be extinct. It is this never-completed project that comprises the current show at N.Y.U.'s Grey Gallery. The curators organized the exhibition by dividing it into subcategories labeled "Mothers," "Fathers," "Children," "Partners," and "Families."

Madalyn Murray in her bedroom, 1964 (Copyright © Estate of Diane Arbus, 1964. Esquire Collection, Spencer Museum of Art, the University of Kansas)

It is fascinating to examine the 57 contact sheets—many shown for the first time in this exhibition—and guess which shots Arbus would select for printing. Inevitably she chose the ones featuring uncomfortable, even freaky-looking people in awkward poses. She neither manipulated images nor employed gimmicks, but simply set up the scenes, culling from them those best illustrating her own view.

Among the mothers she chose, Marguerite Oswald (mother of alleged Kennedy assassin Lee Harvey Oswald) and Madalyn Murray stand out because their notoriety is based on that of their sons. We probably wouldn't know anything about the sweetly smiling Marguerite Oswald if we weren't told who she was. Murray, a well-known atheist who challenged compulsory school prayer on behalf of her son, is portrayed in a particularly homey environment, the scene reminiscent of a Vuillard painting. Clad in a floral housedress, Murray is set against busy wallpaper and a checkered chenille bedspread. Other portrayals of "mothers" appear equally if not more startling. Foremost among these are the stripper Blaze Starr and Mae West, icons of female sexiness, shown uncharacteristically in domestic settings. Most poignant, perhaps, is the platinum blonde bombshell Jayne Mansfield, her arms around her ordinary-looking adolescent daughter, both caught staring uncomfortably and directly into the camera lens. Flora Knapp Dickinson, honorary regent of the Washington Heights Chapter of the Daughters of the American Revolution, provides a strong contrast to the other mothers. With her dowdy long, black dress, hat, string of pearls, and hands clasped in front of her, she stands in a cluttered interior, dominated by upright lines of furniture. You know in an instant what kind of woman she is.

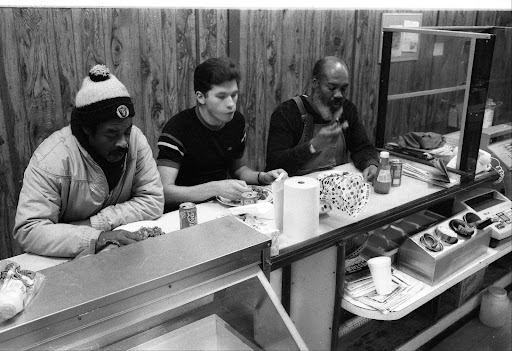

Ozzie and Harriet Nelson, icons of family life on TV during the '50s, are among the "normal" married couples captured by Diane Arbus. Two wonderful photos from 1971 both subtly show Harriet's subservient position to her husband. In one, the two stand happily smiling together. In the second, Harriet appears disgruntled and annoyed, but Ozzie goes on smiling, oblivious to his wife, in a pose identical to the one he struck in the "happy" photo of both of them.

The impetus and core of the show is the commission Arbus received from Gay and Konrad Matthaei, to photograph them and their children in their elegant townhouse. Konrad, a successful TV soap-opera star, and his family made ideal subjects for Arbus, who always found the confluence of public and private persona intriguing. She photographed the family repeatedly over a two-day period, taking 322 photos, following them around during meals, playtime, and family time; she also included a number of more posed shots.

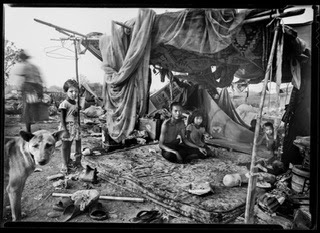

Most striking are the photos of the 11-year-old daughter, Marcella. Dressed in stiff lace, her arms pinned to her sides, she is pictured alone, isolated, standing rigidly in front of a stark wooden backdrop. Her expression is mysterious, not quite frightened, but claustrophobic-looking under her suffocating, long straight hair and bangs. Her younger brother, Konrad, Jr., provides a strong contrast, as he dreamily sits astride his hobbyhorse or cuddles up to his father.

Untitled (Marcella Matthaei), 1969 (Matthaei Collection of Commissioned Famly Photographs by Diane Arbus © Marcella Matthaei Ziesmann)

There are many other striking images in the show: examples include "Santa Claus" with the "real" Mrs. Claus; the "King and Queen" of a senior citizen's dance; the five-times-married midget actor, Andrew Ratoucheff; and Bennett Cerf and Norman Mailer as fathers.

Best known for her grotesque portraits, Diane Arbus often focused her lens on deformed, marginal, or simply unusual personages. What is most interesting about the present show, however, is that she did not choose monsters, but concentrated instead on so-called "normal" people. As always, it is humanity in all its permutations that surfaces here, regardless of categories such as ugly, monstrous, bizarre, or "normal."