By David Steinberg

APRIL 20, 1998: In 1990, the FBI and the San Francisco Police Department raided the studio of Jock Sturges, an art photographer whose work includes portraits of nude children and adolescents. The agents seized Sturges's camera, trashed his studio, and launched an investigation that would, in the end, cost him $100,000 in legal fees.

The art community rallied around Sturges, as did civil libertarians, and a grand jury finally threw the case out. Suddenly more famous and more cautious, Sturges enjoyed a quiet five years until last November, when bookstore protests led by Randall Terry -- better known as the founder of the antiabortion group Operation Rescue -- dragged his work back into the public eye. Grand juries, appalled by pictures they considered obscene in Sturges's Radiant Identities (Aperture, 1994) and British photographer David Hamilton's The Age of Innocence (Aurum, 1995), handed down indictments against Barnes & Noble stores in both Alabama and Tennessee; grand juries elsewhere are reportedly mulling similar action. (For more details on the case, see Michael Bronski's story in this week's One in Ten.)

The two photographers don't share much beyond subject matter and a certain capacity to offend grand juries. Hamilton's work dreamily fetishizes young girls in bed, or by the water; one imagines he can quote whole passages of Lolita from memory, and not the ones about the American landscape. Sturges is different: his photographs, taken among nudist families in California and France, are stark and earnest and conspicuously humane.

David Steinberg conducted the following interview with Sturges between the time of his encounter with the FBI and the current indictments. Sturges's main point here is simple: his portraits take their strength from his subjects' interior lives, and if a lack of clothing makes such a portrait "obscene," perhaps it's the beholder who has, shall we say, issues.

Q: You've said that you don't want to dwell on your legal situation.

A: Not really. The problem with being investigated as invasively as I have been is that you run the risk of having that episode be the defining event in your life. I have no desire to be defined by such assholes, period. What I'm good at is making art. I became good at defending myself, but as far as I am concerned, that was a transient skill. It was an occasion I had to rise to. I'd rather get back to making art than talking about it.

They came, they did not conquer, they went away, and they made me fairly famous in the process. It's no small irony that the government inevitably and invariably ends up promoting precisely that which they would most like to repress.

Q: Has that in fact happened to you?

A: Well, yes and no. My work was doing pretty well before, and now it is doing dramatically better. Is that because people are collecting the pictures because of their notoriety? Or is it simply because people are more aware of the work? I don't know. I'll never get to know.

It's really, really hard to make it as a fine-art photographer exclusively. Now that I have, I'm permanently deprived of the pleasure of knowing whether that's based entirely on my work's merit or whether it's based on my notoriety. That's something that's been stolen from me that I don't get back.

I've been taken to task by some critics for exploiting the whole situation, but that was something I would never have chosen to have happen to me. I have to some extent, perhaps, exploited it, but only because living well was the single revenge presented to me, if that makes any sense. To basically take the opportunity that the feds created for me with their malicious intent and turn it into an advantage -- that feels really good. I went through terrible anguish, as [my work was] derailed by the morbid preoccupation with other people's sexuality that the feds impose on you.

All my life, I've taken photographs of people who are completely at peace being what they were in the situations I photographed them in. In very many cases, that was without clothes, and it simply was not an issue. They were without clothes before I got there, and they were without clothes when I left. That was just a choice that they had made, one they didn't even think about. They were simply more comfortable that way. It never occurred to me that anybody could find anything about that perverse, which is evidence of my having been pretty profoundly naive about the American context. I'm guilty of extraordinary naiveté, I suppose. But it's a naiveté that I really don't want to abandon, not even now.

Q: After you've been through all that, I can't imagine how you can take photographs now without having that somewhere in your mind.

A: There are photographs I don't take now that I previously would have taken without any thought at all.

The truth is that people who are naturists, who are used to being without clothes, are unselfconscious about how they sit around, how they throw themselves down on the ground, how they sit in a chair, how they stand. They don't think about it; it's not an issue. Before, I didn't think there was anything more or less obscene about any part of the body. I'd photograph anything. Now I realize that there are certain postures and angles that make people see red, which are evidence of original sin or something, and I avoid that. But it's difficult.

At one point, Maia [Sturges' wife] found me crossing legs, avoiding angles, giving instructions that inadvertently told young people that some aspect of what they were doing, some aspect of who they were, was inherently profane. I've had to relearn how I work with people so that if I avoid different things, I don't send those messages in doing so. I'm the last person who has any desire to instruct anybody in shame.

Q: The semantics are tricky here, but I'm interested in whether you see your work as erotic. I don't mean erotic as sexual, and I don't mean erotic as intending that people who look at your photos become aroused. But certainly, when I look at many of your photos, when I look at many of Sally Mann's photos, what I see is the natural eroticism of children, or preteens, or teens.

A: Western civilization insists on these concrete demarcations. Before 18, you don't exist sexually; after 18, you exist like crazy. It's ridiculous. The truth is that from birth on, Homo sapiens is, to one extent or another, a fairly sensual species. There isn't a person alive who doesn't like being caressed. Children masturbate as early as one and a half or one year old. They do it spontaneously and without any thought that there's anything evil about making themselves feel good. That's a sensual experience in their lives, one that should remain entirely the property of the child, as it were.

We're really blind in this country. People don't see the extraordinary inconsistencies. I think the average age for the loss of virginity for female children in this country now is something like 141/2 or 15. There's a vast epidemic of unwed mothers and teenage mothers, and yet we have an 18-year-old age of consent, which makes them all felons. If the age of consent were lower, you could talk to these children intelligently and not have to worry about school boards and PTAs going apoplectic if you mention the word condom, let alone sex. As soon as you forbid something, you make it extraordinarily appealing. You also bring in the phenomenon of shame. I'm perpetually exasperated by the American take on sexuality.

To give you a good example of a more intelligent way of doing business: in the Netherlands, the age of consent, I think, is 13, and children younger than that are not militantly discouraged from being sensual human beings. It's not a libertine culture -- it's actually fairly conservative in some ways -- but the Dutch quite intelligently recognize that people become sexually active fairly young in this day and age. One of the results of this is that the incidence of child abuse in Holland is vastly less than it is here. Why? Because children belong to themselves in that culture. If somebody aggresses them -- touches them in a way that's inappropriate -- they'll talk [about it]. They're not ashamed to be physical human beings. Their physical privacy belongs to them, and they tell [when someone violates it], and sexual abusers are caught and stopped and treated and dealt with.

In our society there's so much shame attached to sexuality that sexual abusers here, on the average, have had something like 70 or 100 victims before they're finally caught. In Holland the average is like three or four, because shame is absent and people tell much sooner. So when moral crusaders raise [age of consent] limits, create still higher barriers, they're getting the opposite of what they want. It's very shortsighted, I think, not to understand better how the species works psychodynamically.

Q: Focus a little for me on how that affects how you see your work. Isn't what you're calling the sensuality of children, or pubescent teenagers, a major part of what you go for, of what makes a photo of yours work?

A: I'm an artist who's attracted to a specific way of seeing and a way of being. Any artist involved in their work is going to have a focus in what they do. I am fascinated by the human body and all its evolutions. The images I like best are parts of series that I've started, in some cases, with the pregnancies of the mothers of the children in question, and I continue that series right on through the birth of children to the child that resulted from that first pregnancy. I have series that are 25 years long. I recently photographed a mother of two whom I first photographed when she was the age of her older child.

I have this naive and quixotic hope that in seeing the physical progress from start to "no finish," in looking at the body in all its different changes, looking at the fat-bellied babies becoming thinner children -- they get straight, they get long, they become sticks, they begin to develop, their hips go, the whole process matures -- that people [will] understand that the person occupying that body is more than just a physical object. The pictures don't objectify: they're about the evolution of personality and self as much as they are about the evolution of the body.

My hope is that my work is in some way counter-pinup. A pinup asks you to suspend interest in who the person is and occupy yourself entirely with looking at the body, fantasizing about what you could do with that body, completely ignoring how the person might feel about it. People who make pinup photographs don't care who the woman is, what tragedies or triumphs that person's life might encompass. My work hopefully works exactly counter to that. My ambition is that you look at the pictures and realize what complex, fascinating, interesting people every single one of my subjects is.

Q: Are you surprised when people find your photos erotic?

A: No. Not at all.

Q: And yet you seem to go out of your way to deny that the photos are erotic, to disassociate from collections of photos that are erotic, and so on.

A: Let me make an important distinction here. I will always admit immediately to what's obvious, which is that Homo sapiens is inherently erotic or sensual from birth. But that eroticism and sensuality remain the property of the individual in question up until he or she becomes sexually of age. It's arguable what that age is. If I said for attribution that [coming of age sexually occurred] before 18 years old, I'd be hung, drawn, and quartered in American society, whereas in Europe it would raise no eyebrows at all.

But there's also something else. As soon as the system, or an individual in the system, accuses another individual -- as I was implicitly accused, because there were never any charges brought against me -- the accused is forced into artificial polarities of political posture. I found myself serving a sentence of public denial from the very second the raid on my apartment happened. I had to pretend to be something that, quite frankly, I'm probably not, which is a lily-white, absolutely artistically pure human being. In fact, I don't believe I'm guilty of any crimes, but I've always been drawn to and fascinated by physical, sexual, and psychological change, and there's an erotic aspect to that. It would be disingenuous of me to say there wasn't.

One of the fascinating things for me has been to look at who the accusers are. Because invariably, when somebody becomes interested in your sexuality, in your moral life, they're very often manifesting an attempt to disguise disrepair in their own personal sexual life or morality. It's what I call the trembling-finger syndrome. If somebody's pointing a trembling finger at your pants and saying you shouldn't be doing something, follow that finger back, go up the arm, and look at the head that's behind it, because there's almost always something fairly woolly in there.

Q: How do you work with models, particularly young models, in a way that does not appropriate their sexuality, their eroticism, their sensuality for adult purposes?

A: The transactions between me and the people that I photograph are very, very collaborative. I know the families that I photograph extremely well and have known them for a very long time. The kids really enjoy what they do. I check with them constantly to make sure that they're really happy to be there.

Q: Do they like posing?

A: They adore it. Are you kidding?

Q: What do they like about it?

A: They like being taken seriously as people. After they've been in the process for a while, they realize that they get all the pictures we do -- the families get a copy of every photograph I take -- and they begin to really enjoy being thought of as beautiful.

We live in an age when anonymity is growing in magnitude like a bomb going off. As media stars become increasingly powerful, the rest of us are increasingly ciphers. The distance between the lives [of celebrities] and our lives is growing all the time. Children feel absolutely invisible, unnoticed, as if they can make no difference. The more of the world we see in the media, the more aware we are of how insignificant any one of us is.

Kids feel this, even if they can't articulate it in quite that way. Time and again, when interviewed about being photographed, they talk about the photography as a way of becoming less anonymous. They like the admiration; they like the thought that somebody thinks they can be art.

Now, there's [also] what happens after the photographs are made. It's not hard for me to imagine that there are some [people] who will buy my book, buy my photographs, look at them, and have "impure thoughts." There are people out there who buy shoe ads, Saran Wrap, and all manner of things who have impure thoughts. I can't really do anything about those people, except hope that, if they attend to my work closely enough, they'll ultimately come to realize that these are real people.

What pedophiles and people who have sexual desires for children lose sight of to a terrible, terrible degree -- a devastating degree -- is that their victims are real people who will suffer forever whatever abuses are perpetrated on them. If I'm able to make pictures of children that are so real, as you follow the children growing up over the years, perhaps there will be something cautionary in that visual example. The truth is that every pedophile's victim eventually grows up and becomes an adult who will turn around, and that's when they get caught.

Q: Obviously, your own pursuit of beauty has a lot to do with youth. So what is it about young people that you find so beautiful?

A: There's line, there's androgyny, there's a lot of different things. I've undone the psychological puzzle that is me, and it's not a very complex one. I was sent away to boarding school when I was very, very young, and it wasn't a lot of fun. So I'm particularly fascinated by that age -- the age of my own traumatization, as it were.

Q: What is it about these people that really grabs you? You could be photographing 40-year-old people, or 70-year-old people . . .

A: Well, beyond what I've just said, about what it was that lit the fuse on this work, I'm not really that worried about knowing.

Q: I don't mean what it is about you.

A: I'm letting you know why it is I like what I like.

Q: But what is it you like?

A: It's so different every time, because it evolves. I'm working with a lot of people now who are considerably older than the people I used to work with, because a lot of these kids have literally drawn me up through their lives. I've come to understand that they're even more interesting company and more interesting to photograph -- they're more interestingly complex -- when they're older, when they're in their early twenties and starting to get involved in relationships that may result in children.

When I enter a room, there's always a face or two that will stop me. Everything else is invisible to me; I don't see the other people that are there. There's a certain purity of line. You see the same obsession taken almost to the point of kitsch in English pre-Raphaelite painting. The best of pre-Raphaelite painting is just divine -- very, very pure. You see it in Botticelli, and then you see it in a very different, bitter, beautiful form in the work of my favorite painter, Egon Schiele.

Q: Can you give a picture of how you work with people, your process? Are you directive?

A: The less I direct, the better. People who pose models are really not paying attention to what's beautiful about our species, because poses by definition are limited to the archetypes in our head about how someone should look in a picture. All of which has very little to do, unfortunately, with how we are. People do the most beautiful things imaginable; the less I direct the better.

For me, an ideal shoot is with people I've worked with for a long time. We'll go to a beach or we'll go to a river and we'll spend days there. I interrupt nothing. If people want to go swim, they go swim. If they want to come back, they come back. If they want to leave with their boyfriends, they leave with their boyfriends. If their boyfriends want to be there, if they want to listen to the radio, whatever, I say nothing. I might change a little something, I might turn a head in a larger composition, or change the direction of eyes. Once in a while I'll say, "Don't move," and I'll quickly take a picture. The best photographs always come that way. It's what's the least manipulated and owes the most, therefore, to what the people themselves have done. All the art in my work dwells in the subjects; it's all theirs. It's not made up by me; I ain't that smart.

skip to main |

skip to sidebar

I have been thinking of why I love photography, it comes down to something I have labeled "The Three Joys"

1) Creativity

The first joy is simply creating the work. Everything about the making of photographs I love. The initial ideas, the writing on the blog, the preparation of equipment, the research into my subjects, figuring out what I want to communicate. The camera tech stuff like composition, lens selection, cameras, figuring exposure, taking the shot etc. The post darkroom work where you swim with your prints bringing them slowly to life, creating something powerful and beautiful. I love it all.

It is so powerful a thing, you have a idea in your mind, there is nothing else, then YOU make it, you create it, it's fricking awesome stuff.

2) The People

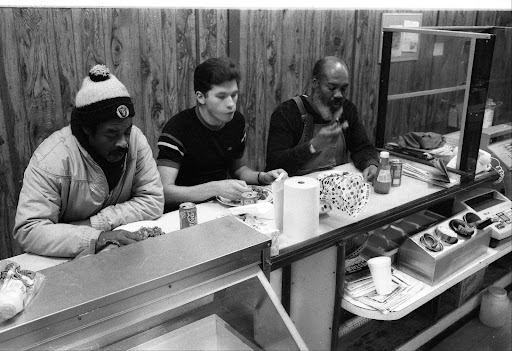

The second joy is that photography has allowed me a way into so many peoples lives, so many different worlds. I get to meet people of all types, speak to them, eat with them, cry and laugh with them. For a while I get to live their existence to be them if you will.

I get to be a child in a slum in Bangkok or a drug addict in a ghetto in Oakland. I get to be a ladyboy sex worker in Pattaya or a man dying of cancer in Canada. Of course I am not really those people but I get a true flavor for those worlds, those experiences, the good and the bad, the ugly and the beautiful, the joy and the sadness.

With photography I get a chance to live outside of the same same everyday meat and potato lives many of my friends and family live. Because I use a camera and make pictures all the doors to a wonderful life experience are open to me, photography is a window into everything!

3) The Photograph

The third joy is about the feeling you get when you accomplish your goals, when you see your final print in the developer, fix or hanging in a gallery. There is a special emotion there, a true satisfied happiness, something so uniquely rewarding. In the darkroom sometimes when I see the finished photo for the first time as it lays in the fixer tray I will let out hoops of joy. I will scream and shout. It is quite a spectacle! It's just the sheer high of that moment bursting out, the YES moment. When the photo is right and you see it for the first time it's the best feeling in the world, better than anything I have ever felt, the high of highs!!

"Ain't Photography Grand!"

"Ain't Photography Grand!!"

Social Documentary Photography for a Better World!

Search This Blog

Contact Gerry Yaum

contact@gerryyaum.net

Gerry Yaum Interview, FRAMES PHOTOGRAPHY MAGAZINE YouTube Channel

"Black & White" Photography Magazine, Issue #160

BLACK &WHITE Magazine, Layout Feature

CENTRE for BRITISH DOCUMENTARY PHOTOGRAPHY, CBDP

St. Albert Gazette MY FATHERS LAST DAYS Story

Me, W. Eugene Smith, Sebastiao Salgado, Lewis Hine and Walker Evans! :) NOT!!!

LUNCHBOX Radio Interview FOR UNB EXHIBITIONS

MONEY EARNED TO HELP THE PEOPLE IN THE PICTURES

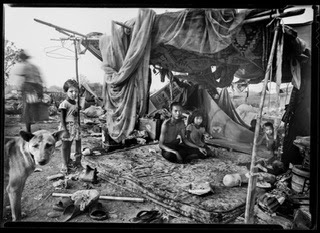

Money that will be used to directly help the people in our two photography projects, THE FAMILIES OF THE DUM and THE PEOPLE WHO LIVE UNDER THE FREEWAY $6334.67 ($6000 earned when 6 prints were added to the UNB permanent collection).

GOFUNDME, FAMILES/FREEWAY

Trying to raise $2000 to help the people under the freeway, and the families of the dump. TOTAL RAISED SO FAR = $325 —->$314.67 (after GOFUNDME fees).

UNIVERSITY OF NEW BRUNSWICK EXHIBITIONS VIDEO

Analog Forever Magazine

Vernon Morning Star Newspaper Story

2022 "Families of the Dump"/The People Who Live Under The Freeway Donation Buys

Total donation money spent for the 2022 trip to the Mae Sot dump (THE FAMILIES OF THE DUMP), Bangkok's Klong Toey Slum (THE PEOPLE WHO LIVE UNDER THE FREEWAY). Money spent on "The Families of the Dump" = $571.17 CAD (14982 Thai Baht) Money spent on "The People Who Live Under The Freeway = $144 CAD (3849 Thai Baht) General cases where money was spent to help others in need $15 CAD (401baht)

(Thai Currency) or

CAD

"Families of the Dump" Donation Total

$4420.02 CAD

GERRY YAUM: YouTube Video PHOTOGRAPHY CHANNEL

THE GOAL

To create photographs that speak to the universality, the commonality and the shared humanity of all peoples, regardless of country, race, culture or language.

TRANSLATE YAUM'S PHOTO DIARY INTO YOUR LANGUAGE

Quote: Robert F. Kennedy

“The purpose of life is to contribute in some way to making things better.”

Quote: Nelson Mandela

"As long as poverty, injustice and gross inequality persist in our world, none of us can truly rest."

Quote: Weegee (Authur Fellig)

"Be original and develop your own style, but don't forget above anything and everything else...be human...think...feel. When you find yourself beginning to feel a bond between yourself and the people you photograph, when you laugh and cry with their laughter and tears, you will know your on the right track....Good luck."

Blog Archive

Total Pageviews

The Three Joys Of Photography

The Three Joys

1) Creativity

The first joy is simply creating the work. Everything about the making of photographs I love. The initial ideas, the writing on the blog, the preparation of equipment, the research into my subjects, figuring out what I want to communicate. The camera tech stuff like composition, lens selection, cameras, figuring exposure, taking the shot etc. The post darkroom work where you swim with your prints bringing them slowly to life, creating something powerful and beautiful. I love it all.

It is so powerful a thing, you have a idea in your mind, there is nothing else, then YOU make it, you create it, it's fricking awesome stuff.

2) The People

The second joy is that photography has allowed me a way into so many peoples lives, so many different worlds. I get to meet people of all types, speak to them, eat with them, cry and laugh with them. For a while I get to live their existence to be them if you will.

I get to be a child in a slum in Bangkok or a drug addict in a ghetto in Oakland. I get to be a ladyboy sex worker in Pattaya or a man dying of cancer in Canada. Of course I am not really those people but I get a true flavor for those worlds, those experiences, the good and the bad, the ugly and the beautiful, the joy and the sadness.

With photography I get a chance to live outside of the same same everyday meat and potato lives many of my friends and family live. Because I use a camera and make pictures all the doors to a wonderful life experience are open to me, photography is a window into everything!

3) The Photograph

The third joy is about the feeling you get when you accomplish your goals, when you see your final print in the developer, fix or hanging in a gallery. There is a special emotion there, a true satisfied happiness, something so uniquely rewarding. In the darkroom sometimes when I see the finished photo for the first time as it lays in the fixer tray I will let out hoops of joy. I will scream and shout. It is quite a spectacle! It's just the sheer high of that moment bursting out, the YES moment. When the photo is right and you see it for the first time it's the best feeling in the world, better than anything I have ever felt, the high of highs!!

"Ain't Photography Grand!"

Contact Gerry

- Gerry Yaum

- Edmonton, Alberta, Canada

- Email Gerry: gerryyaum@gmail.com

"Can a photograph stop a war? Can it save a life? Can it lead to understanding, inspire someone to help, provide comfort and open the door to compassion?

Hope that it can.

Pray that it can."

Hope that it can.

Pray that it can."