Special to Camera Works

The healing passage of time can soften the hard edges of pain and injustice, but that doesn't mean we ever should forget. The writer George Santayana reminds us that those who forget the past are condemned to repeat it. And if a younger generation – be it post-Holocaust Jews, post-revolution Cubanos, post-Velvet Revolution Czechs, post-Birmingham blacks – fail to appreciate fully the sacrifice and circumstance of those who've gone before, it us up to the older among us to remind them.

Bruce Davidson, now a famed Magnum photographer, was a 28 year-old white kid from Illinois in 1961 when he began photographing what has come to be called the Civil Rights struggle in America – when African-Americans sought through voting rights, desegregation and changes in public accommodations laws to claim the birthright of equal opportunity that until then had been only selectively bestowed.

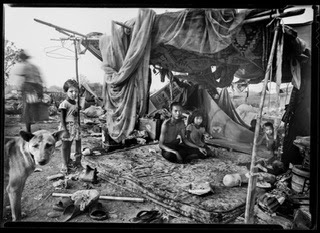

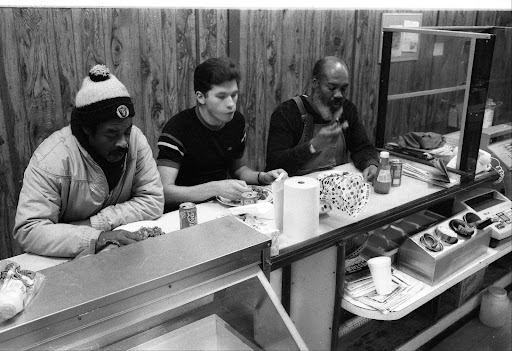

Over four turbulent, violent years – 1961-65 –Davidson documented the struggle: from on board the buses of the Freedom Riders, from sharecroppers' shacks in the rural south, under the guns of national guardsmen, under the glare of racist cops–from peaceful demonstrations in New York City to violent, fire-hosed demonstrations in Alabama.

It was, Davidson said, the most meaningful story he ever covered with his cameras. Asked if he could think of any other event to rival or surpass it, he replied simply "the birth of my children."

Davidson's work from that period – winnowed down to 144 superb black and white photographs – is contained in a just-released book, Time of Change: Civil Rights Photographs, 1961-65 (St. Ann's Press, NYC, $65). It is a powerful documentary of one of the most turbulent periods in modern American history, a period that surpasses even the turmoil of the Vietnam antiwar movement, and certainly the controversy over the political scandal, Watergate, that toppled a sitting president.

At a time when we as a nation are debating how to counter terrorism from abroad, Davidson shows us what it was like for one group of Americans to confront terrorism at home, delivered upon them by their fellow citizens, often under the cover of law.

"The people who really were at risk were those young black demonstrators: sisters and mothers and fathers who might lose their jobs" just for taking part in a march, Davidson said in an interview. And the prospect of violence – not to mention sudden death – never was far away. On the morning Davidson boarded a Trailways bus in 1961 to accompany Freedom Riders on their trip from Montgomery, Ala., to Jackson, Miss., a long line of squad cars and National Guard troops with grim faces and fixed bayonets provided escort. But what comfort did that really provide?

"You knew those troops were white southern boys and you knew where the sympathies of the police were," Davidson recalled. The rifles the Guard carried held live rounds, but "we knew there could be a sniper in the woods and you'd never catch him."

Paranoid? Not really. The week before, another freedom bus, this one in Anniston, Ala., had been set afire and its passengers hauled out and severely beaten.

Remember: in the patriotic fervor that gripped the nation after September 11th we largely were united in colorblind grief and outrage. It also is instructive to recall a time when such widespread unity would have been more difficult to achieve, so great was the divide between what had been called at the time "two societies, one black, one white, separate and unequal." The gulf between the races, wide even now, was a chasm back then and it took people of uncommon courage and conviction to challenge the status quo. Because to do so back then literally could cost you your life, snuffed out with the casual cruelty of a Nazi shooting a Jew in Poland, or of an Albanian killing a Serb in Kosovo (or vice-versa.)

Witness for example Davidson's stark photograph of Viola Liuzzo's bloodstained car.

He writes in his afterword:

"Viola Liuzzo, a 39-year-old white housewife [and mother of four] from Detroit, came down south in her Oldsmobile as a volunteer. She would shuttle marching students to their homes in nearby communities. One night she was delivering one last marcher, when she was shot in the face at close range by the Klan...."

"Early the next morning I stood at the crime scene. As I moved closer to her car, which had run off the highway, I could see where the driver's side window was completely shattered, and where blood had dripped down the front seat and dried in a dark stain...As I continued to take pictures, a state trooper approached me with his hand on his gun holster. He waved me to move away."

I think back to that time – when I was in college in New York and when other, braver, of my counterparts were joining the Freedom Riders down south – and marvel at a courage I never could imagine. "It was a terrorist atmosphere," Bruce Davidson remembered, "but what replaced that terror was the dignity and patience of those marchers and demonstrators."

For Davidson personally the experience was dangerous up to a point – after all, he was white and he could get the hell out of Dodge whenever he felt like it, and no one would fault him. No, Davidson told me, "the real danger that counts is the danger of confronting your own prejudices. I began to feel very close to African Americans on an individual basis" because of the coverage over those years – and it shows in these riveting images.

What sets this book apart from other chronicles of the time is its quiet. That is: juxtaposed with images of confrontation and hatred are images chronicling the black experience in a number of cities, north and south: images that are gentle, dignified, joyous, sorrowful – all achingly, wonderfully human.

They illustrate well Davidson's credo, which has served him so well for so long, to show "the presence of the photographer, but not the camera."

Still, in every controversial, hair-trigger, news story such as the civil rights struggle, the legitimate question arises of how much the press influences, or even causes, events. Two instructive views, the first from Bruce Davidson, describing a tense, potentially violent scene during the '63 Mississippi Freedom March:

"At a rest stop along the roadside a marcher named Winston sat down. A group of ...white youths surrounded him. Winston attempted to talk to them. One lit a match and tossed it down at him. I had to be cautious, standing there with my Leica, not to precipitate violence. I didn't want the youths to perform for the camera; slowly I put it to my eye clicking a couple of frames...."

Ultimately the tension eased. There was no violence – at least not that day.

But for the last word, here is Rep. John Lewis (D-Ga.), a veteran of the struggle, who served at the side of Martin Luther King and who wrote this in the foreword to Davidson's remarkable book:

"I truly believe that our acts of nonviolent resistance, along with the contributions of reporters and photographers, had an impact....Without the media and without those powerful images, I don't know where we'd be today....It was the unbelievable photographs published in newspapers and magazines that literally brought people from around the globe to small Southern towns to join the movement, inspired by those amazing pictures."