I have been studying the work of EJ Bellocq lately, he was a hack pro photographer from New Orleans who in 1912 did some private work. The personal work was a wonderful series of portraits of the prostitutes working the Storyville red light district. He was discovered long after his death by the photographer Lee Freelander. I am searching for some of his books online, the joy/sadness/frankness he gives these woman is something I am going to work towards, I want to give a more rounded view of who my subjects are.

I found this article by Nan Goldin online and thought I would post it.

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Bellocq Epoque - photographer E.J. Bellocq

Nan Goldin

NAN GOLDIN ON THE "STORYVILLE PORTRAITS"

Late one Berlin night in 1991, a famous German fashion photographer invited me and two friends to join him for a trip to Bel Ami, his favorite brothel in the Grunewald. The presence of a woman as a customer created a ripple of surprise, but the photographer, being a regular and popular visitor, put them at ease. Glossy prints of his published photographs of the house, group portraits of the "girls" who worked there and the pimp ("host"), were hanging on the walls. Though the setting was a German villa, the props were familiar: patterned wallpaper, heart-shaped velvet pillows, mirrors, chandeliers, gilded Turkish figurines holding red lamps, pink fleshy faux-Baroque nude paintings. One could imagine the same prevalence of gold and red in the brothels of Storyville, the red-light district of New Orleans in the early part of the century.

We drank overpriced splits of cheap champagne with the girls in the living room while chatting about the most mundane aspects of Berlin life. Finally, while the photographer was otherwise engaged, my friend, a shy poet, and I hired a beautiful young Brazilian woman to take us to a room. She stripped to her G-string while we sipped champagne and I questioned her about her life history. She kept asking us what we wanted her to do. I asked if I could take some photographs, and shot a few pictures of the decor of the rooms, and then of her nude and smiling, at ease on the round bed. I wanted these images to come as close as they could to the experience of her having to be intimate with strangers, like putting myself in the position of a john without forcing any sexual transaction. The experience of photographing her served as sublimation for the act of caressing her velvet skin. We each kissed her, paid her, and left. A gallery in Los Angeles recently exhibited a wide variety of photographs of prostitution that included one of these pictures of Linda from Bel Ami. The artists represented ranged from Brassai to Lisette Model to Mary Ellen Mark to Philip-Lorca diCorcia, but on the cover of the invitation, appropriately enough, was an image by E.J. Bellocq, the remarkable early-twentieth-century photographer of the Storyville whorehouses whose pictures are among the most profound and beautiful portraits of prostitutes ever taken.

In October 1996 a gorgeous new book of Bellocq's photographs was published by Random House, much to the delight of all who have known his work since the early '70s. Eighteen photos have been added to the thirty-four that were included in Storyville Portraits, put out by the Museum of Modern Art in 1970 on the occasion of a survey of Bellocq's work. The frontispiece is new: a charming picture of two women in their underwear playing cards in an opulent room. This elegant book, a collaboration between the brilliant editor Mark Holborn and photographer Lee Friedlander, is also in a larger format - the same size of the original glass plates - than the earlier publication, allowing one to see the details of the interiors with clarity and inviting entry into the world of Storyville. The printing in tritone instead of duotone permits much more gradation and subtlety in the print quality. The book is as sensual and seductive as the women in it.

Without Friedlander's intervention, no one would know the work of E.J. Bellocq. A frequent visitor to the Crescent City to photograph the jazz scene, Friedlander was friends with a compulsive collector named Larry Borenstein, who owned an art gallery in the '50s. One night Borenstein showed Friedlander a number of the glass plates, which were among his collections and from which he had made some ordinary 8 x 10 prints that he sold around town for about $100 apiece. Apparently, the plates had been discovered in a drawer in one of Bellocq's desks when the contents of his apartment were sold after his death. A number had incurred water damage, and some were damaged by the cracking of the glass itself during Hurricane Betsy in 1965 (many of these cracks weren't evident in the rare earlier prints). Friedlander couldn't forget these images, and felt they should be preserved and seen. So in 1966, he bought the plates from Borenstein. When one thinks of the massive amount of negatives and glass plates one comes across in flea markets and thrift shops, Friedlander's power of discrimination becomes even more admirable, rivaling Berenice Abbott's rescue of Eugene Atget's work from oblivion. As a prominent photographer himself (and, like all artists, undoubtedly always behind in his own work), it is exceptional that Friedlander took the time and energy to research the appropriate printing technique for plates from that period. With this work-intensive method he printed a total of eighty-nine images. He took them to magazines and book publishers, one of whom told him they could only be published on the condition that Tennessee Williams write the introduction. Finally, John Szarkowski at the Museum of Modern Art agreed to exhibit Friedlander's prints and publish the book, Storyville Portraits.

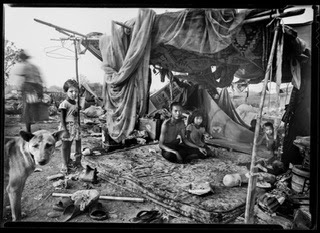

The body of Bellocq's portraits has been dated to around 1912, a period of legal bordellos in Storyville (women lived in these houses and were subject to arrest for working outside the quarter). Although little is known about Bellocq, many believe that the pictures were taken at Lulu White's Mahogany Hall (the wallpaper in some of the photos apparently matches that from White's whorehouse). Bellocq takes us into the brothel, one that is thought to have been a high-class joint frequented by prominent men. In those days, guides to the various brothels in Storyville called "Blue Books" were occasionally illustrated with photographs and euphemistically describing the girls' talents in Victorian language ("she serves amber fluid, reads poetry beautifully"). Although some believe that Bellocq may have made the photographs with the intention of publishing them in one of these catalogues or on a commercial assignment, the fact is that they remained hidden away until after his death.

At the turn of the century, prostitution was an even more unusual subject for photography than today, and the experience of being photographed was far different. At that time, it would have been a special occasion, a form of attention that required time and collaboration. In spite of the large, unwieldy 8 x 10 camera, Bellocq's pictures appear natural, and the women seem open and trusting. There's a nonthreatening presence with an unprecedented degree of empathy permeating his work, rather than the usual sense of someone in a power position objectifying his or her subject. Bellocq's photos do not show prostitution as a reductive identity. As well as the many straightforward portraits, there are also pictures that are like a playful game: both parties were fully engaged and indulging in layers of fantasy and self-creation. With the women's obvious trust, warmth, and ease, these pictures transcend the normal customer-to-prostitute relationship, and therefore one must assume Bellocq and the women shared a greater than usual degree of familiarity and intimacy.

Bellocq never betrays his respectful and nonjudgmental position in his portayal of the women. That they are prostitutes does not preclude the fact that some of them are shown as ordinary young women. They seem to have posed themselves, choosing from an enormous variety of identities. Some pose like Pre-Raphaelite heroines, others like college girls with school banners, while some recline in interiors as opulent as Turkish opium dens. There are girls in gymnasts' outfits, in pantaloons and homely nightcaps, and others hold their little pet dogs. There are thin young girls more passive and childlike in their nudity, a la Pretty Baby, the 1978 Louis Malle film supposedly based on Bellocq. Many are ladies dressed in all their finery who look like they are on their way to a garden party. One woman is pictured as a virginal saint with eyes downcast, cradling a huge bouquet, almost like a religious painting. A wide variety of body types are shown with the same reverence and lack of judgment, including women with the voluptuous flesh of Rubens' bodies, which is rare in the history of the male representation of the female nude in photography. And unlike other male photographers - from Weston to Cartier-Bresson tO Strand to Friedlander - Bellocq never severs the head from the female nude in the shot. There are domestic scenes that evoke Vermeer, where one sees the details of the girls' lives in their personal mementos, the steamer trunks, the bedclothes and the laundry. There's a touch of perverse sexuality in some, in which the women, totally nude, wear masks. But the most expressive photos are those overflowing with a casual sensuality, where the woman's bodice is dropping off, proudly exposing her breasts, while her whole being is filled with radiant innocence. One of these pictures, of a woman with bare legs in a silk camisole and curls and a delighted smile, is the most joyous photograph I have ever seen taken of a prostitute.

Contradicting the effervescence of much of the work, many more of the disturbing photographs in which the women's faces are intentionally scratched out have been included in this new book. While the willful destruction of photographic images of the body in contemporary art has become a kind of artful, self-conscious trend, in Bellocq's case, this bizarre and savage act seems to be some kind of personal censorship. In art school in the '70s, I had been taught that Bellocq's brother, a Jesuit priest, had been the culprit, though that theory seems to be disputed now. Some theorize that Bellocq himself scratched the glass negatives while they were still wet, either out of the desire to protect somone's identity or some emotional outburst or jealousy. I think it's highly unlikely that he would have done this to his own work, so lovingly made, and if he had wanted to hide the identity of some of the women, he could have used masks, as he did in some of the pictures. The theory that one of the girls may have done it out of jealousy or a desire to deny the intimacy she had previously been engaged in seems most likely to me, although it could be called into question by the fact that in a few places pictures of the same girl occur with her face both intact and deleted. In the end, the defaced pictures add a darkness that could represent a visual metaphor for violence against women that is in direct contrast to the warmth and tenderness of the book as a whole.

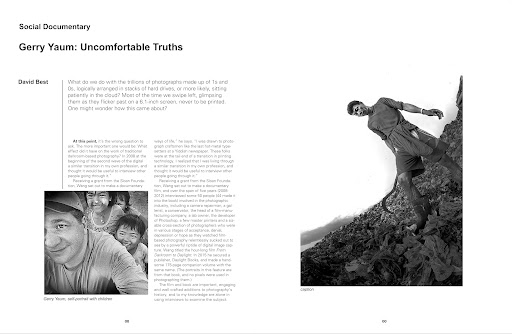

Much has been made throughout the years of Bellocq's supposed identity and its relationship to the women he photographed. Until recently, photographic history described him as a "hydrocephalic semi-dwarf," largely based on an imaginary discussion, patched together from letters and excerpts from recorded conversations, that John Szarkowski published in both the original and the recent versions of the book. Szarkowski's discussants include Friedlander, a writer named Al Rose, jazz musicians, old photographers from the Quarter, and Adele, the subject of several of Bellocq's photographs. They describe him as a kind of peculiar, Toulouse-Lautrec-like figure with a very high head that came to a point, who spoke in a high-pitched voice and walked in little mincing steps. This description of him as a physically nonthreatening and asexual man, different from the others who would have frequented the brothels, has often served as an explanation for why the work is so empathic and intimate. When I asked Friedlander what he knows about Bellocq personally, he answered, "I'm not interested in the man, I'm interested in the pictures." He recommended I call Steven Maldansky, curator of photographs at the New Orleans Museum of Art, who has done extensive research on Bellocq while organizing an exhibition of the photographer's life as well as his Storyville work. On the basis of an image of Bellocq published in a turn-of-the-century magazine, Maklansky contends that the description of him as physically abnormal is exaggerated, and that he was indeed a debonair young man with a moustache who did not look so different from the photographer played by Keith Carradine in Pretty Baby. Rex Rose, whose research Maklansky drew on when compiling his exhibition, found Bellocq's hospital records, which describe him at seventy-six, not long before his death in 1949, as a "normal, well-developed male."

What is known about his life is that he was born Ernest J. Bellocq in 1873 to a middle-class Catholic Creole family. His father was a bookkeeper, and his brother Leo became a priest. Bellocq dropped out of Jesuit college at age eighteen to become a clerk and bookkeeper. He took up photography as a hobby in the early 1890s, and had a career for twenty or thirty years as a commercial photographer, taking mundane pictures of sports teams, graduation classes, and first communions. Around World War I, he photographed shipbuilding companies and machinery parts. He joined the New Orleans Camera Club and had work published in various magazines and newspapers. At the same time he was photographing Catholic schoolgirls, he would have been making these Storyville pictures, and there is also a rumor that he photographed in the opium dens in the Chinatown of New Orleans, though these plates have never been discovered. He was a prominent though not hugely successful amateur, and had some family money. A lifelong batchelor, he lived with his mother a block and a half from Storyville until her death in 1902, after which he moved just a few blocks away. Above his mantelpiece, which is shown in a photograph in the book, hung many photographs of women, vignetted and framed as close-up portraits of their faces. Some of them seem to be among the fifteen or twenty women included in "Storyville Portraits." One of the houses where he lived in the '30s is thought to actually have had a whorehouse in it. In the '30s the shy and reclusive Bellocq retired, but was said to make daily rounds of the camera stores, becoming one of the many familiar eccentrics that the Quarter is known for. His cause of death is not known but seems to have resulted from either falling down a flight of stairs or being hit by a car.

Regardless of the mythology surrounding Bellocq, whether he was a dwarf or an ordinary man, whether his familiarity at Lulu White's was based on being a customer or a confidant, the genius of his work cannot be diminished. Some people have ascribed the pleasure evident in the women from being photographed by him as mirth at his physical deformity. Maklansky theorized that his obviously nonthreatening relationship was motivated by his paying them. Since most interpersonal transactions for a prostitute involve the exchange of money, it takes more than money to make a prostitute smile. I know that prostitution, especially today, can be a dangerous and potentially self-destructive job. Whatever Bellocq's intentions were, whatever the nature of his relationship to these women, his portraits transcend the portrayal of the prostitute as an object. I imagine that, with his loving gaze, the desire and the sexual act that normally occurs in prostitution had been sublimated into the act of photographing. In the end "Storyville Portraits" remains a unique collection of love poems.

Special thanks to Lee Friedlander and Steven Maklansky.