Found this interesting article today on the photography site Casual Photophile ( Author? written 2015). The piece is about the ethics of photographing the homeless. My fake name comes up in the comment section (thanks Dave). The article is worth a read, lots of varying opinions on this delicate subject. The are you exploiting or not exploiting argument is a regular point that comes up on most all social documentary photography sites, links, photo exhibitions, artist talks etc. It something I have wrestled with in the past. It is something I will probably talk about at my artist talk on the 31st.

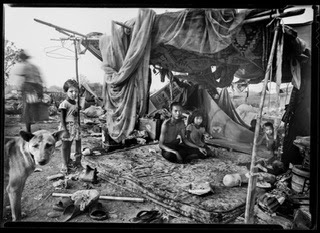

My argument is simple. Social documentary photography leads to positive change. Photographs do make a difference they can even help stop wars (2 images from Vietnam were highly influential by Nick Ut and Eddie Adams helped stopped that war - you know the photos). Photographing a forgotten life, telling that persons story (with their permission of course) is hugely important, Making a piece that lives on past the photographer and subjects lifetime that continues the fight against injustice is the highest form of beauty. Putting your camera down and not making the picture furthers the closing of societies eyes to the problem. We need opened eyes, not closed eyes or nothing ever changes.

https://www.casualphotophile.com/2015/06/19/on-photographing-the-homeless-a-dialogue/

My argument is simple. Social documentary photography leads to positive change. Photographs do make a difference they can even help stop wars (2 images from Vietnam were highly influential by Nick Ut and Eddie Adams helped stopped that war - you know the photos). Photographing a forgotten life, telling that persons story (with their permission of course) is hugely important, Making a piece that lives on past the photographer and subjects lifetime that continues the fight against injustice is the highest form of beauty. Putting your camera down and not making the picture furthers the closing of societies eyes to the problem. We need opened eyes, not closed eyes or nothing ever changes.

https://www.casualphotophile.com/2015/06/19/on-photographing-the-homeless-a-dialogue/

SHOULD WE PHOTOGRAPH THE HOMELESS?

It’s my belief that a writer’s job is to ask questions. As the owner of a camera shop and the founder of CP, I spend a lot of time thinking about photography, cameras, and what it means to make pictures. But for more than a year now, a certain question has been gnawing at me that pertains to the craft and ethics of street shooting, and after a year of occasional rumination I’m no closer to an answer. Specifically, the question involves photographing the downtrodden, impoverished and homeless among us.

So without judgement, condescension, or pretense, I’d like to air some thoughts on the topic and hear what our readers have to say. Maybe together we can work out what it means (if indeed it means anything) to photograph those less fortunate than ourselves, and whether or not we should do it in the first place.

If you’re into street photography you’ve likely heard both sides’ vehement proclamations, so let’s examine the most common arguments for and against the practice of photographing the homeless.

Many who defend the making of this kind of photo are likely to first cite their right as a photographer to capture the world as they see it, and if that world happens to contain a homeless man begging for food, so be it. On the face of it, this is true. But let’s take a closer look at the “it’s my right” argument. While a photographer does indeed have the right to photograph people and things that are out in public spaces and within public view, this right doesn’t grant the right to impinge upon another’s rights. Get it? For the sake of this conversation, the right that’s potentially violated by a street photographer is a person’s right to a reasonable expectation of privacy.

When we talk about violating a person’s reasonable expectation of privacy it’s very easy to agree what is a violation, but it’s much more difficult to say what is not. For example, shooting through the bathroom window of a private residence to photograph someone taking a shower is immoral, unethical, and illegal, and it’s an obvious violation of a person’s privacy. On that we can all surely agree. But when we start to talk about shooting photos of the homeless things get a little less obvious and a lot more controversial. That’s because it’s much more difficult to define what is and is not a person’s private property if they, in fact, own no property.

In the absence of a place to live, a homeless person has no choice but to be subject to the whims of the public, including those who would photograph them. Without the protective domain of private property, a homeless person has no choice but to be perpetually on display. He or she is without privacy virtually 100 percent of the day. That’s the cold reality. But is that just the way it is? Does a person’s homelessness automatically forfeit their right to privacy? If yes, why? And if not, where exactly does their private space begin and end?

In past conversations with photo geeks, I’ve heard people callously remark that if the homeless don’t want to be photographed they should “get a home.” This is certainly a perspective shared by many, even if many don’t come right out and say it. I find it difficult to align myself in that camp. I don’t pretend to understand all of the massively complex causes and ramifications of homelessness, but I can’t help feel that this kind of dismissive flippancy toward those who are homeless is arrogant at best, despicable at worst, and always a repellant vocalization of an ignorant mind.

There’s an inverse school of thought that says the homeless are in a perpetual state of occupying their own private space. By virtue of their lacking any traditional private space of their own, they in essence occupy an invisible bubble of private space wherever they happen to be. By this logic, shooting a photo of any homeless person in any situation is an ethical transgression and a violation of that person’s reasonable expectation of privacy. If you’re a photographer who adheres to this school of thought, any photo of a homeless person is an illegitimate work. I find it difficult to align my thinking with this perspective as well. Surely there are situations in which privacy is voluntarily relinquished by a person?

We’re no closer to an answer.

To keep pushing forward, we can also discuss any social commentary that may be provided through photos of the homeless. Some say that to avoid photographing the homeless is to do a greater disservice than would be done by photographing them. The idea is that these marginalized, mistreated people are already overlooked and ignored by a society to which they’re mostly invisible, and that failing to show them as they are will further encourage this ignorance.

I can understand this idea. Without grit, without dirt, all modern metropolises seem to gleam with brilliant light. The towering skyscrapers and gorgeous buildings stretch above made men and cosmopolitan women, all in perfect clothes. When all we see is sparkling glass and gleaming cars, every city seems like heaven. Were every street shot to show only the beauty of city life we’d have a very warped perception of what it means to exist in an urban area. There needs to be a counter-point to the glamour. I get that. But while I may understand and appreciate the importance of showing the darker side of modern life, I can’t help feel that the homeless just aren’t the right subject.

Without trying to insult anyone, isn’t it safe to assume that if we asked a first-year college student to illustrate the extreme antipode of Wall Street they’d likely take you directly to a homeless shelter? I don’t know if they would, I’m only asking. It just seems like the most obvious demonstration of the counterpoint of affluence. As photographers, shouldn’t we shrink away from the obvious? It seems to me that if a photographer’s looking to illustrate the dirtier side of a city, if he’s really looking to show the grit, a shot of a homeless man sleeping under a Wall Street Journal is low-hanging-fruit indeed.

An artist, whether a painter, sculptor, or photographer, is never interested in the obvious. That’s the true genius of the artist. He or she sees something no one else noticed and presents it in a way that makes the viewer understand the importance of what he overlooked. A true artist takes an ordinary object, a person, an idea, manipulates it, and then shows it to others in a way that makes them wonder, how’d I miss that?

So if the idea is to show the contrast between the “Haves” and the “Have-nots”, if the idea is to show just how difficult life can be, can’t we do it in a less obvious way? Shouldn’t we try a little harder to figure out a way of illustrating the point without exploiting a person who’s quite literally at the lowest rung of society’s ladder?

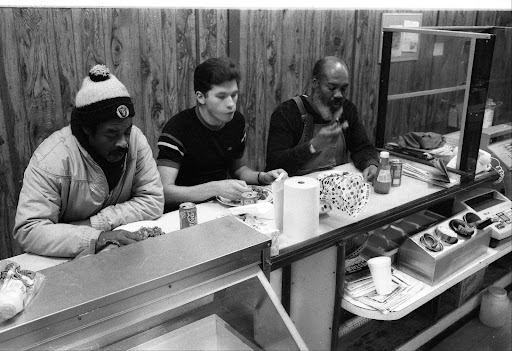

I really don’t know. And the reason I don’t know is because there are some exceptionally talented photographers out there who have done incredible work with the homeless as their subjects. Steve Huff, of the well-known website that bears his name, has just such a project. Where his work differentiates itself from the majority of uncommitted attempts is in its affirmation of these persons’ humanity. His work is more than just a snapshot of a homeless guy. His work is an introduction to a man, a telling of a story, and an earnestly presented lesson.

And there are others who strive to tell the stories of the marginalized and destitute, and do so very effectively. The unifying thread that’s woven throughout the very fabric of these masters’ shots seems to be a respectfulness of their subjects. To me, the photographers who understand how to respect a person’s innate rights are the ones who manage to make compelling shots of the homeless. If a photographer lacks this ability, perhaps it’s best to try a different subject. Does this mean those of us with less talent don’t have the right to shoot the homeless? I’m not sure. As I said, this is a topic for me which inevitably leads to more questions. If you’ve spent some time thinking on it, let me know what you’ve come up with in the comments. Perhaps with your insight I can suss out my feelings and decide on a protocol for the future.

For now, I’ll keep avoiding those obvious shots and continue to regard the homeless as unfortunate souls who deserve respect and privacy. And if respecting another human being’s privacy means limiting the subjects I can photograph, that’s alright with me. Hell, if I never take a decent photo again they’ve still got it a lot worse than I.

So what do you think? Should we, or should we not make the homeless into subjects of our art? Sound off in the comments.

FRANCIS.R.

June 19, 2015 at 6:28 amI liked the Steve Huff’s series because they are seeing the camera with dignity, with eyes that say that being poor doesn’t make you miserable, nor a saint neither.