Thursday, October 30, 2008

Quote: Minor White

" The reason why we want to remember an image varies: Because we simply "love it", or dislike it so intensely that it becomes compulsive, or because it has made us realize something about ourselves, or has brought about some slight change in us. Perhaps the reader can recall some image, after the seeing of which he has never been quite the same."

Wednesday, October 29, 2008

Hong Kong Photographs

Thinking more and more lately about the work I want on the coming 3 week trip to Hong Kong. Not sure on what kind of photos I can make there, it is a bit out of my element.

Will have to develop a theme to the images as I learn more about that world.

Thinking more and more about Africa, I want to go make photos somewhere on that continent, where? not sure!

I so want to make some important photographs, some photos that will make a difference, photographs that will inspire and that will help me grow as a person and also allow others to understand what I have seen and felt when they view the images.

Will have to develop a theme to the images as I learn more about that world.

Thinking more and more about Africa, I want to go make photos somewhere on that continent, where? not sure!

I so want to make some important photographs, some photos that will make a difference, photographs that will inspire and that will help me grow as a person and also allow others to understand what I have seen and felt when they view the images.

Quote: Alfred Stieglitz

Looking at Minor's (Minor White) prewar photographs, he asked, "Have you ever been in love?" Minor said yes, and Stieglitz told him, "Then you can photograph."

Monday, October 20, 2008

Blads and Leica's

Been doing a bit of Ebay bidding lately on high end camera systems. One of the positive side benefits of the digi photo revolution is people are dumping their Leica and Hasselblad equipment at reduced prices.

For years I have not been able to purchase high end Hasselblad and Leica M6 rangefinder systems, but now the pricing situation has changed! Bring on the blads and M6 cameras boys!!

I want to get these cameras and start making photographs as soon as possible. The main reasons I am loading up on these systems is that the cameras are very well made and rarely break down (I have had some breakdown issues lately) and the lens for these systems are the best in the world, nothing beats a lens that is sharp and has wonderful contrast.

I plan on taking a Blad 501c and Leica M6 with 3 lens to Hong Kong in mid November to make some photographs.

For years I have not been able to purchase high end Hasselblad and Leica M6 rangefinder systems, but now the pricing situation has changed! Bring on the blads and M6 cameras boys!!

I want to get these cameras and start making photographs as soon as possible. The main reasons I am loading up on these systems is that the cameras are very well made and rarely break down (I have had some breakdown issues lately) and the lens for these systems are the best in the world, nothing beats a lens that is sharp and has wonderful contrast.

I plan on taking a Blad 501c and Leica M6 with 3 lens to Hong Kong in mid November to make some photographs.

Sunday, October 19, 2008

Quote: Michelangelo

"What you have to strive for with all your means, a great deal of hard work and a willingness to learn by the sweat of your brow, is to make the work you produce with such pains look as if it was dashed off easily, quickly, and virtually without effort-even if that is not the case."

Friday, October 17, 2008

Great Online Articles

The Washington Post has some wonderful online articles about photography written by Mr. Frank Van Ripper check them out here:

http://www.washingtonpost.com/wp-srv/photo/essays/vanRiper/riperArchive.htm

http://www.washingtonpost.com/wp-srv/photo/essays/vanRiper/riperArchive.htm

Thursday, October 16, 2008

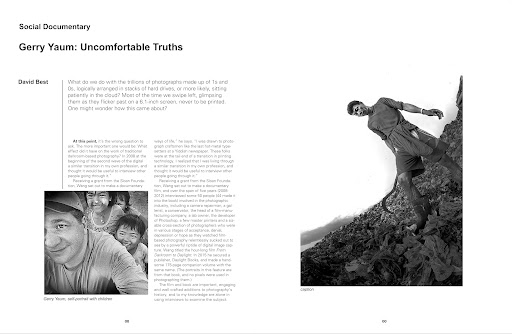

Bruce Davidson's Powerful 'Time of Change'

By Frank Van Riper

Special to Camera Works

The healing passage of time can soften the hard edges of pain and injustice, but that doesn't mean we ever should forget. The writer George Santayana reminds us that those who forget the past are condemned to repeat it. And if a younger generation – be it post-Holocaust Jews, post-revolution Cubanos, post-Velvet Revolution Czechs, post-Birmingham blacks – fail to appreciate fully the sacrifice and circumstance of those who've gone before, it us up to the older among us to remind them.

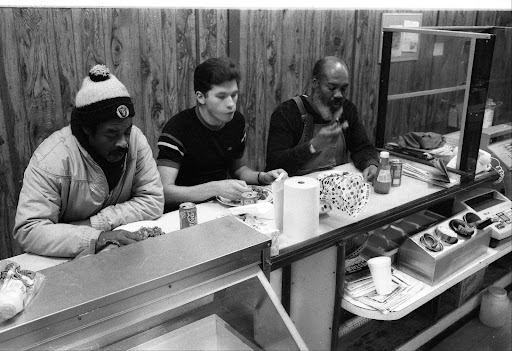

Bruce Davidson, now a famed Magnum photographer, was a 28 year-old white kid from Illinois in 1961 when he began photographing what has come to be called the Civil Rights struggle in America – when African-Americans sought through voting rights, desegregation and changes in public accommodations laws to claim the birthright of equal opportunity that until then had been only selectively bestowed.

Over four turbulent, violent years – 1961-65 –Davidson documented the struggle: from on board the buses of the Freedom Riders, from sharecroppers' shacks in the rural south, under the guns of national guardsmen, under the glare of racist cops–from peaceful demonstrations in New York City to violent, fire-hosed demonstrations in Alabama.

It was, Davidson said, the most meaningful story he ever covered with his cameras. Asked if he could think of any other event to rival or surpass it, he replied simply "the birth of my children."

Davidson's work from that period – winnowed down to 144 superb black and white photographs – is contained in a just-released book, Time of Change: Civil Rights Photographs, 1961-65 (St. Ann's Press, NYC, $65). It is a powerful documentary of one of the most turbulent periods in modern American history, a period that surpasses even the turmoil of the Vietnam antiwar movement, and certainly the controversy over the political scandal, Watergate, that toppled a sitting president.

At a time when we as a nation are debating how to counter terrorism from abroad, Davidson shows us what it was like for one group of Americans to confront terrorism at home, delivered upon them by their fellow citizens, often under the cover of law.

"The people who really were at risk were those young black demonstrators: sisters and mothers and fathers who might lose their jobs" just for taking part in a march, Davidson said in an interview. And the prospect of violence – not to mention sudden death – never was far away. On the morning Davidson boarded a Trailways bus in 1961 to accompany Freedom Riders on their trip from Montgomery, Ala., to Jackson, Miss., a long line of squad cars and National Guard troops with grim faces and fixed bayonets provided escort. But what comfort did that really provide?

"You knew those troops were white southern boys and you knew where the sympathies of the police were," Davidson recalled. The rifles the Guard carried held live rounds, but "we knew there could be a sniper in the woods and you'd never catch him."

Paranoid? Not really. The week before, another freedom bus, this one in Anniston, Ala., had been set afire and its passengers hauled out and severely beaten.

Remember: in the patriotic fervor that gripped the nation after September 11th we largely were united in colorblind grief and outrage. It also is instructive to recall a time when such widespread unity would have been more difficult to achieve, so great was the divide between what had been called at the time "two societies, one black, one white, separate and unequal." The gulf between the races, wide even now, was a chasm back then and it took people of uncommon courage and conviction to challenge the status quo. Because to do so back then literally could cost you your life, snuffed out with the casual cruelty of a Nazi shooting a Jew in Poland, or of an Albanian killing a Serb in Kosovo (or vice-versa.)

Witness for example Davidson's stark photograph of Viola Liuzzo's bloodstained car.

He writes in his afterword:

"Viola Liuzzo, a 39-year-old white housewife [and mother of four] from Detroit, came down south in her Oldsmobile as a volunteer. She would shuttle marching students to their homes in nearby communities. One night she was delivering one last marcher, when she was shot in the face at close range by the Klan...."

"Early the next morning I stood at the crime scene. As I moved closer to her car, which had run off the highway, I could see where the driver's side window was completely shattered, and where blood had dripped down the front seat and dried in a dark stain...As I continued to take pictures, a state trooper approached me with his hand on his gun holster. He waved me to move away."

I think back to that time – when I was in college in New York and when other, braver, of my counterparts were joining the Freedom Riders down south – and marvel at a courage I never could imagine. "It was a terrorist atmosphere," Bruce Davidson remembered, "but what replaced that terror was the dignity and patience of those marchers and demonstrators."

For Davidson personally the experience was dangerous up to a point – after all, he was white and he could get the hell out of Dodge whenever he felt like it, and no one would fault him. No, Davidson told me, "the real danger that counts is the danger of confronting your own prejudices. I began to feel very close to African Americans on an individual basis" because of the coverage over those years – and it shows in these riveting images.

What sets this book apart from other chronicles of the time is its quiet. That is: juxtaposed with images of confrontation and hatred are images chronicling the black experience in a number of cities, north and south: images that are gentle, dignified, joyous, sorrowful – all achingly, wonderfully human.

They illustrate well Davidson's credo, which has served him so well for so long, to show "the presence of the photographer, but not the camera."

Still, in every controversial, hair-trigger, news story such as the civil rights struggle, the legitimate question arises of how much the press influences, or even causes, events. Two instructive views, the first from Bruce Davidson, describing a tense, potentially violent scene during the '63 Mississippi Freedom March:

"At a rest stop along the roadside a marcher named Winston sat down. A group of ...white youths surrounded him. Winston attempted to talk to them. One lit a match and tossed it down at him. I had to be cautious, standing there with my Leica, not to precipitate violence. I didn't want the youths to perform for the camera; slowly I put it to my eye clicking a couple of frames...."

Ultimately the tension eased. There was no violence – at least not that day.

But for the last word, here is Rep. John Lewis (D-Ga.), a veteran of the struggle, who served at the side of Martin Luther King and who wrote this in the foreword to Davidson's remarkable book:

"I truly believe that our acts of nonviolent resistance, along with the contributions of reporters and photographers, had an impact....Without the media and without those powerful images, I don't know where we'd be today....It was the unbelievable photographs published in newspapers and magazines that literally brought people from around the globe to small Southern towns to join the movement, inspired by those amazing pictures."

Special to Camera Works

The healing passage of time can soften the hard edges of pain and injustice, but that doesn't mean we ever should forget. The writer George Santayana reminds us that those who forget the past are condemned to repeat it. And if a younger generation – be it post-Holocaust Jews, post-revolution Cubanos, post-Velvet Revolution Czechs, post-Birmingham blacks – fail to appreciate fully the sacrifice and circumstance of those who've gone before, it us up to the older among us to remind them.

Bruce Davidson, now a famed Magnum photographer, was a 28 year-old white kid from Illinois in 1961 when he began photographing what has come to be called the Civil Rights struggle in America – when African-Americans sought through voting rights, desegregation and changes in public accommodations laws to claim the birthright of equal opportunity that until then had been only selectively bestowed.

Over four turbulent, violent years – 1961-65 –Davidson documented the struggle: from on board the buses of the Freedom Riders, from sharecroppers' shacks in the rural south, under the guns of national guardsmen, under the glare of racist cops–from peaceful demonstrations in New York City to violent, fire-hosed demonstrations in Alabama.

It was, Davidson said, the most meaningful story he ever covered with his cameras. Asked if he could think of any other event to rival or surpass it, he replied simply "the birth of my children."

Davidson's work from that period – winnowed down to 144 superb black and white photographs – is contained in a just-released book, Time of Change: Civil Rights Photographs, 1961-65 (St. Ann's Press, NYC, $65). It is a powerful documentary of one of the most turbulent periods in modern American history, a period that surpasses even the turmoil of the Vietnam antiwar movement, and certainly the controversy over the political scandal, Watergate, that toppled a sitting president.

At a time when we as a nation are debating how to counter terrorism from abroad, Davidson shows us what it was like for one group of Americans to confront terrorism at home, delivered upon them by their fellow citizens, often under the cover of law.

"The people who really were at risk were those young black demonstrators: sisters and mothers and fathers who might lose their jobs" just for taking part in a march, Davidson said in an interview. And the prospect of violence – not to mention sudden death – never was far away. On the morning Davidson boarded a Trailways bus in 1961 to accompany Freedom Riders on their trip from Montgomery, Ala., to Jackson, Miss., a long line of squad cars and National Guard troops with grim faces and fixed bayonets provided escort. But what comfort did that really provide?

"You knew those troops were white southern boys and you knew where the sympathies of the police were," Davidson recalled. The rifles the Guard carried held live rounds, but "we knew there could be a sniper in the woods and you'd never catch him."

Paranoid? Not really. The week before, another freedom bus, this one in Anniston, Ala., had been set afire and its passengers hauled out and severely beaten.

Remember: in the patriotic fervor that gripped the nation after September 11th we largely were united in colorblind grief and outrage. It also is instructive to recall a time when such widespread unity would have been more difficult to achieve, so great was the divide between what had been called at the time "two societies, one black, one white, separate and unequal." The gulf between the races, wide even now, was a chasm back then and it took people of uncommon courage and conviction to challenge the status quo. Because to do so back then literally could cost you your life, snuffed out with the casual cruelty of a Nazi shooting a Jew in Poland, or of an Albanian killing a Serb in Kosovo (or vice-versa.)

Witness for example Davidson's stark photograph of Viola Liuzzo's bloodstained car.

He writes in his afterword:

"Viola Liuzzo, a 39-year-old white housewife [and mother of four] from Detroit, came down south in her Oldsmobile as a volunteer. She would shuttle marching students to their homes in nearby communities. One night she was delivering one last marcher, when she was shot in the face at close range by the Klan...."

"Early the next morning I stood at the crime scene. As I moved closer to her car, which had run off the highway, I could see where the driver's side window was completely shattered, and where blood had dripped down the front seat and dried in a dark stain...As I continued to take pictures, a state trooper approached me with his hand on his gun holster. He waved me to move away."

I think back to that time – when I was in college in New York and when other, braver, of my counterparts were joining the Freedom Riders down south – and marvel at a courage I never could imagine. "It was a terrorist atmosphere," Bruce Davidson remembered, "but what replaced that terror was the dignity and patience of those marchers and demonstrators."

For Davidson personally the experience was dangerous up to a point – after all, he was white and he could get the hell out of Dodge whenever he felt like it, and no one would fault him. No, Davidson told me, "the real danger that counts is the danger of confronting your own prejudices. I began to feel very close to African Americans on an individual basis" because of the coverage over those years – and it shows in these riveting images.

What sets this book apart from other chronicles of the time is its quiet. That is: juxtaposed with images of confrontation and hatred are images chronicling the black experience in a number of cities, north and south: images that are gentle, dignified, joyous, sorrowful – all achingly, wonderfully human.

They illustrate well Davidson's credo, which has served him so well for so long, to show "the presence of the photographer, but not the camera."

Still, in every controversial, hair-trigger, news story such as the civil rights struggle, the legitimate question arises of how much the press influences, or even causes, events. Two instructive views, the first from Bruce Davidson, describing a tense, potentially violent scene during the '63 Mississippi Freedom March:

"At a rest stop along the roadside a marcher named Winston sat down. A group of ...white youths surrounded him. Winston attempted to talk to them. One lit a match and tossed it down at him. I had to be cautious, standing there with my Leica, not to precipitate violence. I didn't want the youths to perform for the camera; slowly I put it to my eye clicking a couple of frames...."

Ultimately the tension eased. There was no violence – at least not that day.

But for the last word, here is Rep. John Lewis (D-Ga.), a veteran of the struggle, who served at the side of Martin Luther King and who wrote this in the foreword to Davidson's remarkable book:

"I truly believe that our acts of nonviolent resistance, along with the contributions of reporters and photographers, had an impact....Without the media and without those powerful images, I don't know where we'd be today....It was the unbelievable photographs published in newspapers and magazines that literally brought people from around the globe to small Southern towns to join the movement, inspired by those amazing pictures."

Avedon: The Roar of an Aging Lion

By Frank Van Riper

Special to Camera Works

It was in the 1970s, Dennis Brack recalled, as he made ready to photograph Ronald Reagan after the Florida Republican primary. Brack, one of the best in the business, was shooting for Time Magazine and knew Reagan well. Conversation with the ex-governor, film star and then-presidential candidate came easily.

That was quite a famous photographer who was here the other day, Brack declared. [Coincidentally, Brack's photo shoot came shortly after Reagan, the ex-movie star who never met a camera or a photographer he didn't like, had posed for Richard Avedon.]

"He wasn't very good," Reagan told Brack. The actor/politician then described Avedon's bulky view camera equipment and his unique-some might call it excruciating– portrait style.

"He was very slow," Ronald Reagan said.

Richard Avedon will turn 80 next year and for much of his life he has been fired by anxiety and the compulsion to make images. When he was a child growing up in New York in a prosperous Jewish household [his father and his uncle owned Avedon's of Fifth Avenue, a chic women's specialty shop] he sometimes would tape paper profiles to his skin so that the faces would remain on his sunburned body.

He remembers having an eye twitch that annoyed his family, but recalls too that the constant blinking was a way for him to make still pictures in his mind.

"It comes in the genes," Richard Avedon once said.

The tendency is to think of Avedon as one thinks of Picasso: an artist who has gone through many periods, each in its own way significant and successful. His fashion work, for Harper's Bazaar, Mademoiselle and Vogue, gave the staid fashion world of the 50s a deserved kick in the pants. Who else would photograph a gorgeous, willowy, dressed-to-the-nines model in between two elephants? (Well, Steichen actually, but he used a horse.)

His editorial photography, appearing not only in these magazines, but decades later in magazines from Rolling Stone to the New Yorker, always had a characteristic style that made you know the work was his.

His advertising work, often in color, was lush yet also edgy, and done with the help of an invisible army of stylists and assistants.

But, even with the inevitable overlap among these genres, it likely will be Avedon's more personal work that shapes his huge legacy when finally he is gone.

Richard Avedon: Portraits, on display at New York's Metropolitan Museum of Art through January 5th, distills this great photographer's work in a way that surely he desired. The elaborate fashion sets are gone; banished too are the environmental portraits showing a subject in his or her milieu. This distillation of more than a half century of work is itself a distillation-of style.

"I've worked out a series of No's," Avedon tells visitors to his show in a text block on the wall. "No to exquisite light, No to apparent composition, No to the seduction of poses or narrative. And all these No's force me to the Yes. I have a white background. I have the person I'm interested in and the thing that happens between us." Thus there now are on the gallery wall only the subjects and the seamless backdrop, most often dead white, but occasionally a shade of grey. Full-length, three-quarter, close-up–most often singly, but at times in groups. Nothing but the person-no context to shape our opinion, no background to guide our thought. Just the person and what that person brought to the portrait session, whether he or she knew it or not.

To some this will call to mind "In the American West," Avedon's riveting documentation of everyday people from an area that surely was as alien to a native New Yorker as Manhattan would be to a cowboy. Just as surely one could think of his searing portraits of those we've come to know through notoriety, fame or a combination thereof– pictures that always offer a take we've never seen before, but once seen this way, cannot be ignored or forgotten:

A withering view of the Duke and Duchess of Windsor-a profile of well-dressed languor and weakness; a lost Marilyn Monroe, her perfect breasts haltered in sequins, her gaze vacant, her pouty lips parted; A pensive, even somber Groucho Marx after all the jokes have been told, seemingly confronting his own mortality.

Even Ronald Reagan, as always standing at attention in a dark blue suit, but with a questioning gaze that seems to ask: "are you sure this is what you want?"

Over the years Avedon has weathered criticism for these supposedly cruel or confrontational portraits. Criticism too for allegedly standing sphinx-like behind his formidable view camera until his subject weakens and takes an action or adopts a pose or expression that may be visually interesting but surely out of character. And, certainly, the pictures on the walls of the Met are strong, and often disturbing.

But cruel? No, they are not cruel. What they are is powerful in a way that confronting one's own humanity as well as the humanity of others we know or admire can be devastating.

It needs to be remembered, and repeated, that in photography, especially in portrait photography, the final image is always-always–collaboration. Only one who draws or paints has total control over the final rendering. That is the real power to be cruel.

In a 1985 taped interview with Connie Goldman to coincide with "In the American West," Avedon described perfectly, I think, how this collaboration works:

"A portrait photographer depends on another person to complete his picture...he is willing to become implicated in a fiction he can't possibly know about..."

"My concerns are not [my subject's]," Avedon went on. "We have separate ambitions for the image.

"His [the subject's] need to plead his case probably goes as deep as my need to plead mine. But the control is with me."

That control, as well as his talented eye, has enabled Richard Avedon to capture expressions and gesture that seem uncannily right, even if in so doing he might seem heartless. "I've looked for the humanity in all of the people I've photographed," Avedon has said-and it is hard not to believe him.

The process itself is fascinating, as well as instructive-though one gets to that in small pieces and in snippets from assistants. Like many artists guarding their magic, Avedon has little desire to tell-all about how he actually does it.

But this we do know....

For "In the American West" Avedon worked with an 8x10 view camera. His subjects stood outdoors against a white backdrop. Avedon rarely engaged his subjects in conversation once they were selected-from newspaper advertisements, or from Avedon's own personal observation.

But once before the camera, as one of his subjects recalled, "You never really noticed the camera-you felt his presence even behind the lens." An assistant recalled that from behind the camera, Avedon's body often would "take on the appearance of the person he [was] photographing."

"I'm best in short takes that are intense," Avedon told interviewer Goldman, adding that when he is photographing someone, the subject has to feel as if he or she "is the most important person in the world at this moment...they've got to feel that."

This is not the m.o. of someone aiming to be cruel–or ironic or superior. This is the modus operandi of one of the greatest portraitists of our time.

The Metropolitan show, drawn from actual exhibition prints from previous shows, is dominated by Avedon's now-signature monumental prints. Interestingly, two walls are devoted to much smaller images, of politicians and other public figures, made around the 70s. These are some of the weakest pieces here, but not because they are small. My sense is that pols and public figures are less likely than others to let any but their cultivated persona be caught on film.

Shortly after the Avedon show opened, photographer Neil Selkirk, who knows Avedon, wrote to his colleague and said this about the western portraits, though his thoughts could apply to almost everything on the walls:

"Individually they are exquisite and absorbing, as a group they are a collection of monoliths; as the Pyramids or Stonehenge are to architecture, nothing that follows (or precedes them) in photographic portraiture can be considered without reference to them. Can there be a more enduring achievement?"

I certainly can think of none.

Richard Avedon: Portraits. Through January 5. Metropolitan Museum of Art, Fifth Avenue at 82nd St, New York City (212-879-5500) Tu-Su, 9:30-5:30; Fri and Sa evenings until 9.

Frank Van Riper is a Washington-based commercial and documentary photographer and author. His latest book is Talking Photography (Allworth Press), a collection of his Washington Post columns and other photography writing over the past decade. He can be reached through his website www.GVRphoto.com.

The Collectors: Liz Jobey

Liz Jobey guardian.co.uk, Thursday October 09 2008 13.10 BST Article history

Ronald Reagan, former governor of California, March 4 1976, by Richard Avedon. Photograph: © 2008 The Richard Avedon Foundation

Many of the photographic portraits that Richard Avedon took in the course of his long and celebrated career are bound up with the idea of fame. His subjects were frequently figures in public life, and being photographed by him served to reinforce their celebrity. Portraits of Power, the title of a new book published three years after Avedon's death to celebrate election year in America, presumably refers both to the power his subjects wielded and to the power Avedon's style of photography conferred upon them. For the most part this involved the subject being asked to stand against a white (or in some cases grey) backdrop, while the photographer, having prepared the plate in his 8"x10" camera, stood next to it, enjoying the freedom it gave him to talk to his subjects before pressing the shutter, encouraging them to relax and, as he admitted, sometimes gesturing, or taking a stance which they consciously or unconsciously imitated, thereby producing the picture he wanted.

Frank H Goodyear, associate curator of photography at the Smithsonian Institution, as part of his essay in the book, asked some of Avedon's subjects for their reactions to the experience of being photographed and to the results. What is quickly apparent is their realisation of how far he had preconceived the way they would look: "He knew what he wanted… He came in with a concept …" (John Kerry, US senator, Massachusetts), "He obviously knew what he wanted and he knew how to get it…" (Jerry Brown, former governor of California). "He must have had a picture in his mind…" (Dorothy Zellner, civil rights activist). Though most of them recognised some semblance of themselves, one or two felt they had been set up. Karl Rove, George W Bush's former chief strategist, complained: "The portrait is foolish, stupid, insulting. It makes me look like a complete idiot."

At several periods throughout Avedon's working life he turned his attention away from fashion and advertising towards politics, notably in the late 1960s, when he began a long project on America's counter-culture movement, photographing members of protest groups and left-wing activists. This included a famous multiple portrait of the Chicago Seven, accused of inciting riots at the 1968 Democratic Convention. The portrait is a triptych, a composite of three prints spliced together so that some of the figures overlap. It is reminiscent, as has often been said, of a police identity lineup.

The Chicago Seven: Lee Weiner, John Froines, Abbie Hoffman, Rennie Davis, Jerry Rubin, Tom Hayden, Dave Dellinger, Chicago, September 25, 1969, by Richard Avedon. Photograph: © 2008 The Richard Avedon Foundation In 1971, Avedon travelled to Vietnam where he made another composite portrait of the 11 members of the US Mission Council, an ironic companion &piece to the Chicago Seven. In 1976 he filled a special issue of Rolling Stone magazine with 69 portraits of members of America's "power elite". In the early 1990s he photographed the surviving members of the Kennedy court, and in 2004, another election year and the year of his death, he began a political project which he called Democracy, a cross-section of public figures and laymen who made up what he called, optimistically, "people-powered politics". For the first time he chose to make some of the pictures in colour. Among these, just two months before he died, was the keynote speaker at the Democratic national convention in Boston: the senator for Illinois, Barack Obama.

The writer Renata Adler, who collaborated with Avedon on the Rolling Stone portrait project, describes his overpowering desire to "make" the photograph he wanted. In most cases, she explains, the sitter's and the photographer's intentions were not radically different, but there were exceptions. Years before, when a conflict had arisen between the Duke and Duchess of Windsor as to how they wanted to look and how Avedon wanted them to be seen, Avedon told Adler he had "made up a sad story about dogs to get the dour expressions he was after".

He was interested in surface and surface detail, in evidence (the title of his 1994 Whitney Museum retrospective), in the marks that time and personal experience had left on a face, and in the ease or awkwardness with which a subject presented him or herself before the camera. He positioned them within a narrow designated area between the white backdrop and the lens (Ronald Reagan apparently required chalk marks to tell him where to stand), flashed a bright light in their faces and pressed the shutter. He wasn't concerned to find the "real" person, Adler writes. He wanted "to take a picture, a masterpiece. An Avedon."

What results in this book, which collects portraits from the early 1950s to his final work in 2004, is a sometimes relentless cavalcade of middle-aged and older men in suits (there are relatively few women) punctuated by hippies, yippies and representatives of late 1960s liberal politics who protested against the Vietnam war, racism, capitalism, and inequality. In large part, Avedon shared their concerns; to be attracted by fame and power did not mean that he admired or condoned the means of its acquisition. But afterwards he felt that the early project hadn't succeeded. "I photographed hundreds of people in the late '60s peace movement," he told Sally Quinn of the Washington Post in 1976, "and none of them stand up."

One of the characteristics of his pictures is that, though his subjects are required to stand calmly, hands to their sides, not smiling, they give off a kind of glamour, the same glamour that comes so effortlessly to his fashion pictures. As portraits they exude such confidence, such clarity; their subjects are stranded in a sea of white, with every pore, every wrinkle, every wart exposed. But they are portraits devoid of sympathy. Despite the attention to detail, gathered together they begin to acquire the role of specimens, pinned to the page by an energetic visual anthropologist, keen to add them to his collection.

Many of the subjects here are long past the height of their fame - names such as Kissinger, Ford, Kennedy, Bush Snr, George Wallace, Robert McNamara, Ronald Reagan - but their portraits still hold a horrible fascination. Not all the pictures are strong: some are weak, such as the one of Salman Rushdie; there are few happy portraits (Karl Rove is smiling, but inanely); there are eerie portraits and ones of people who are used to being photographed, such as Patti Smith or Sean Penn. And there is Barack Obama, a portrait of a man trying to look calm without giving away any clues at all.

Ronald Reagan, former governor of California, March 4 1976, by Richard Avedon. Photograph: © 2008 The Richard Avedon Foundation

Many of the photographic portraits that Richard Avedon took in the course of his long and celebrated career are bound up with the idea of fame. His subjects were frequently figures in public life, and being photographed by him served to reinforce their celebrity. Portraits of Power, the title of a new book published three years after Avedon's death to celebrate election year in America, presumably refers both to the power his subjects wielded and to the power Avedon's style of photography conferred upon them. For the most part this involved the subject being asked to stand against a white (or in some cases grey) backdrop, while the photographer, having prepared the plate in his 8"x10" camera, stood next to it, enjoying the freedom it gave him to talk to his subjects before pressing the shutter, encouraging them to relax and, as he admitted, sometimes gesturing, or taking a stance which they consciously or unconsciously imitated, thereby producing the picture he wanted.

Frank H Goodyear, associate curator of photography at the Smithsonian Institution, as part of his essay in the book, asked some of Avedon's subjects for their reactions to the experience of being photographed and to the results. What is quickly apparent is their realisation of how far he had preconceived the way they would look: "He knew what he wanted… He came in with a concept …" (John Kerry, US senator, Massachusetts), "He obviously knew what he wanted and he knew how to get it…" (Jerry Brown, former governor of California). "He must have had a picture in his mind…" (Dorothy Zellner, civil rights activist). Though most of them recognised some semblance of themselves, one or two felt they had been set up. Karl Rove, George W Bush's former chief strategist, complained: "The portrait is foolish, stupid, insulting. It makes me look like a complete idiot."

At several periods throughout Avedon's working life he turned his attention away from fashion and advertising towards politics, notably in the late 1960s, when he began a long project on America's counter-culture movement, photographing members of protest groups and left-wing activists. This included a famous multiple portrait of the Chicago Seven, accused of inciting riots at the 1968 Democratic Convention. The portrait is a triptych, a composite of three prints spliced together so that some of the figures overlap. It is reminiscent, as has often been said, of a police identity lineup.

The Chicago Seven: Lee Weiner, John Froines, Abbie Hoffman, Rennie Davis, Jerry Rubin, Tom Hayden, Dave Dellinger, Chicago, September 25, 1969, by Richard Avedon. Photograph: © 2008 The Richard Avedon Foundation In 1971, Avedon travelled to Vietnam where he made another composite portrait of the 11 members of the US Mission Council, an ironic companion &piece to the Chicago Seven. In 1976 he filled a special issue of Rolling Stone magazine with 69 portraits of members of America's "power elite". In the early 1990s he photographed the surviving members of the Kennedy court, and in 2004, another election year and the year of his death, he began a political project which he called Democracy, a cross-section of public figures and laymen who made up what he called, optimistically, "people-powered politics". For the first time he chose to make some of the pictures in colour. Among these, just two months before he died, was the keynote speaker at the Democratic national convention in Boston: the senator for Illinois, Barack Obama.

The writer Renata Adler, who collaborated with Avedon on the Rolling Stone portrait project, describes his overpowering desire to "make" the photograph he wanted. In most cases, she explains, the sitter's and the photographer's intentions were not radically different, but there were exceptions. Years before, when a conflict had arisen between the Duke and Duchess of Windsor as to how they wanted to look and how Avedon wanted them to be seen, Avedon told Adler he had "made up a sad story about dogs to get the dour expressions he was after".

He was interested in surface and surface detail, in evidence (the title of his 1994 Whitney Museum retrospective), in the marks that time and personal experience had left on a face, and in the ease or awkwardness with which a subject presented him or herself before the camera. He positioned them within a narrow designated area between the white backdrop and the lens (Ronald Reagan apparently required chalk marks to tell him where to stand), flashed a bright light in their faces and pressed the shutter. He wasn't concerned to find the "real" person, Adler writes. He wanted "to take a picture, a masterpiece. An Avedon."

What results in this book, which collects portraits from the early 1950s to his final work in 2004, is a sometimes relentless cavalcade of middle-aged and older men in suits (there are relatively few women) punctuated by hippies, yippies and representatives of late 1960s liberal politics who protested against the Vietnam war, racism, capitalism, and inequality. In large part, Avedon shared their concerns; to be attracted by fame and power did not mean that he admired or condoned the means of its acquisition. But afterwards he felt that the early project hadn't succeeded. "I photographed hundreds of people in the late '60s peace movement," he told Sally Quinn of the Washington Post in 1976, "and none of them stand up."

One of the characteristics of his pictures is that, though his subjects are required to stand calmly, hands to their sides, not smiling, they give off a kind of glamour, the same glamour that comes so effortlessly to his fashion pictures. As portraits they exude such confidence, such clarity; their subjects are stranded in a sea of white, with every pore, every wrinkle, every wart exposed. But they are portraits devoid of sympathy. Despite the attention to detail, gathered together they begin to acquire the role of specimens, pinned to the page by an energetic visual anthropologist, keen to add them to his collection.

Many of the subjects here are long past the height of their fame - names such as Kissinger, Ford, Kennedy, Bush Snr, George Wallace, Robert McNamara, Ronald Reagan - but their portraits still hold a horrible fascination. Not all the pictures are strong: some are weak, such as the one of Salman Rushdie; there are few happy portraits (Karl Rove is smiling, but inanely); there are eerie portraits and ones of people who are used to being photographed, such as Patti Smith or Sean Penn. And there is Barack Obama, a portrait of a man trying to look calm without giving away any clues at all.

Monday, October 13, 2008

Enviromental Portraits

Been to tired lately to add much to the blog. I got a paying gig to do enviromental portraits at a petrochemical plant. It is quite a bit of fun to make these images, it involves going to many places I have never been before while photographing the workers. I am wearing all kinds of safety gear which is a bit of a challenge in itself. Taking photographs with a hardhat, steel toe boots, ear plugs, safety glasses (great on the focusing!), gas detector and 2 way radio is quite an experience!!

Having fun making the photos and also will make some decent money on this project. I can pay off some old photo debts and maybe have enough left over to buy myself a newer used Hasselblad system off Ebay.

I am also using available light mixed with flash more than I ever have before in these portraits. I plan on useing a similiar lighting setup when I do photographs in Hong Kong in November, hopefully with my new/used blad.

Having fun making the photos and also will make some decent money on this project. I can pay off some old photo debts and maybe have enough left over to buy myself a newer used Hasselblad system off Ebay.

I am also using available light mixed with flash more than I ever have before in these portraits. I plan on useing a similiar lighting setup when I do photographs in Hong Kong in November, hopefully with my new/used blad.

Saturday, October 4, 2008

Self Published Books!

Been working on something new lately. I have been putting together some layouts for some self published books! I am using the Internet site www.blurb.com. Blurb prints books for people interested in self publishing, they help you create the books using their downloadable software for Mac or PC. I have been having lots of fun with this, the rates are quite cheap (hope the book quality is not!).

I plan on putting together two books at the present time. The first book will be simple and staight forward and be titled "Sex Worker" it will contain the 2007 Sex Worker images, many of which have not yet be posted on my website. This book will run under 80 pages. The second book will be a major project of 200-400 pages and include work from the last 10 years of my photography. I plan on including diary notes, contact sheets, quotes and hundreds of photographs.

Not sure if I want to try to sell the books or just do it for myself and give it as a gift to people that have helped me through the years with my photography, will see!

I plan on putting together two books at the present time. The first book will be simple and staight forward and be titled "Sex Worker" it will contain the 2007 Sex Worker images, many of which have not yet be posted on my website. This book will run under 80 pages. The second book will be a major project of 200-400 pages and include work from the last 10 years of my photography. I plan on including diary notes, contact sheets, quotes and hundreds of photographs.

Not sure if I want to try to sell the books or just do it for myself and give it as a gift to people that have helped me through the years with my photography, will see!

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)